The Babbling Idiot & The Tribe

Did psychedelics guide human evolution, or is the Stoned Ape Theory just for stoners?

Welcome to Essay Architecture. This essay is about a fringe theory on psychedelics and human evolution, but I want to open with a preamble that links it into my Pattern Language framework:

All the thinking here stems from a particular book (Food of the Gods) by a particular thinker (Terence McKenna), and so this whole essay was conceived as a Response. There are many ways to fulfill a pattern. A Response could be as simple as including a single paragraph that connects your original Thesis to an existing work. On the other hand, an essay can systematically break down a book, respond to each point, and use it as a gateway into a completely new idea. That’s what this is.

So from here you have two options: 1) you can read this 5k word essay on a strange theory that still haunts me, or 2) if you’re a paid subscriber, you can read about the Response pattern in more detail. The vision for the paid tier is to share deep dives of my framework, essay reviews (Here is New York), literary criticism (Best American Essays?), and commentary on writing software. (On deck is a post called “45 predictions on writing in 2045,” and also essays on the Form and Voice dimension.)

This essay is too long for some email providers, so you might want to read this in a browser or on the Substack app. Link here.

The Stoned Ape Theory is too weird for real scientists to take seriously, too convenient for psychedelic activists to doubt, and too catchy for anyone to forget.

Almost everyone I ask about it knows the gist: human consciousness emerged from monkeys eating mushrooms (or some variation of that). It’s basically preposterous. Similar to how the Victorian minds of the 19th century just couldn’t bear the thought of ape ancestors, it’s equally weird to think our minds bloomed from fungus. The Origin of Species (1859) faced decades of resistance; now it’s obvious. New paradigms of evolution are hard to swallow.

Unlike Darwin’s theory though, the Stoned Ape Theory is based on unhinged speculation, spreading mostly through its catchiness. It’s in the opening animation of official Joe Rogan YouTube clips. It’s made popular by entertainers (watch: Bill Hicks in 1993). It’s the subject of Comedy Central shorts. It’s animated in Netflix documentaries. Now, this evolutionary hunch occupies a small sliver in many of our heads, whether we believe it not.

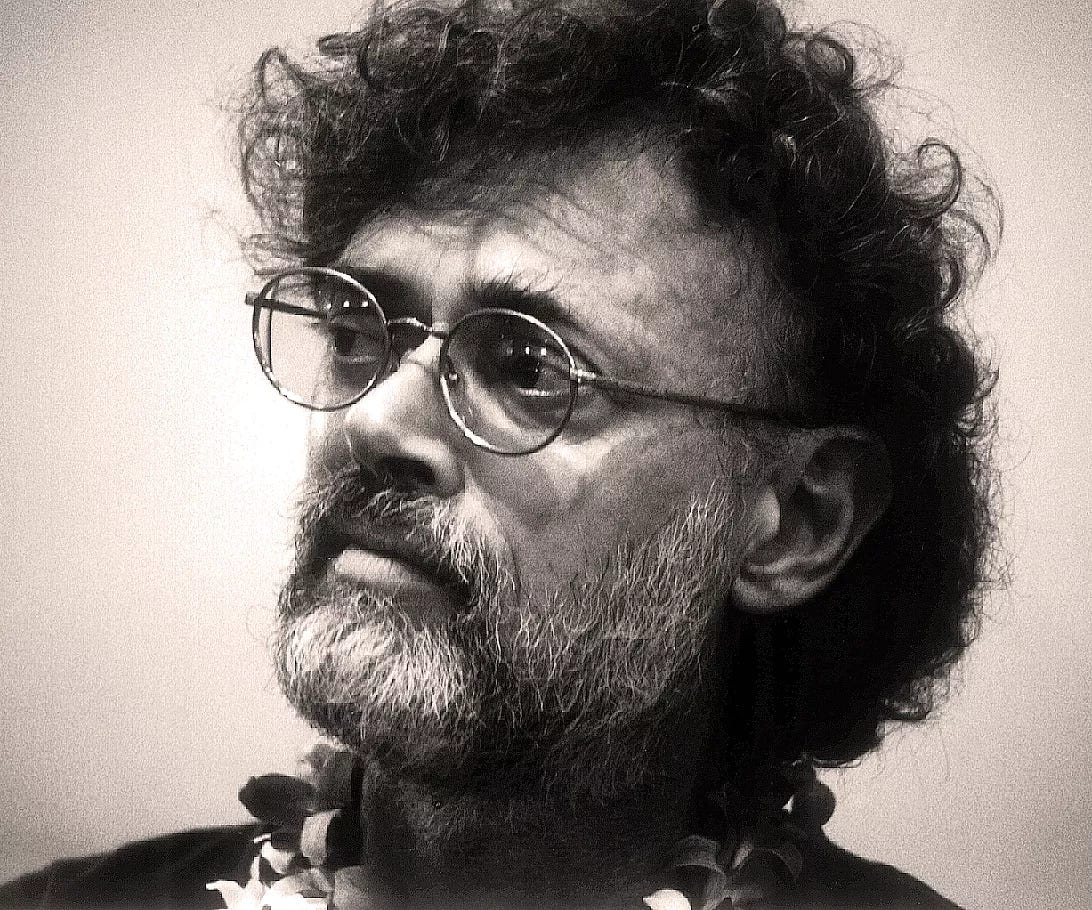

Despite how popular the theory is, most don’t know where it comes from. A memetic virus rarely points back to its source. In this case, it originated in Food of the Gods, a 1992 book by Terence McKenna—who happens to be one of my favorite thinkers.

I’ve listened to 100+ hours of McKenna lectures in the last decade, but didn’t read a full book of his until last year. He’s something like the Grateful Dead in philosopher form (a psychonautic, encyclopedic bard); just as the band’s live shows are better than their albums, McKenna would riff for hours, weaving through radical theories, trip reports, and audience questions, all in a mytho-poetic-comedic style that triggered an audience roar every 60-90 seconds.

Food of the Gods is his most popular book by tenfold, and so I chose to read it first because I wanted clarity on his most known idea: the Stoned Ape Theory. How could a psychedelic trip get into the genome?

The concept always intrigued me but the details never made sense, and so I hoped his 332 pages of careful research and writing could unpack it for me. I browsed Goodreads reviews before diving in, and was disappointed to learn that no such rigor existed:

"Possibly the worst researched book I've ever read, it is nonetheless a fascinating meditation on a variety of radical ideas."

“Whether the musings of a fungus-obsessed false prophet or [an]... invite into the realm that granted sentience to our great ape ancestors, Food of the Gods is a must read, and a must discuss.”

"Rambling, ridiculous, and incoherent.”

After finishing it myself I can confirm that Food of the Gods is a disappointing read, even to a seasoned McKenna fan. It’s more like psychedelic propaganda than anthropological research. It’s also a structural mess that seems to miss the point: only 13% of the book covers the Stoned Ape Theory (I was expecting something like Sapiens on shrooms, but evolution was only the focus in 3 of the 17 chapters).

All that said, within the book is a kernel of an idea that’s not worth abandoning just yet.

It seems likely and significant that pre-lingual humans were exposed to psychedelics during a critical evolutionary moment two million years ago, but McKenna has no serious explanation for how this moved us “out of the stream of animal evolution and into the fast-rising tide of language and culture.” (p. xvii)

While his evolutionary mechanism is flimsy, I’m still haunted by his premise: in the shit of the beasts we hunted grew psilocybin mushrooms, something that looks like an innocent food source, but actually triggers a linguistic explosion.

In the last 33 years, the Stoned Ape Theory has been rightly critiqued, but wrongly dismissed. It’s a bold and weird idea, filled with lots of holes, but it hovers around a perennial mystery: our origins. Now that I’ve finished the book, my sense is that McKenna surfaced some important ideas without convincingly connecting them. The goal of this review of Food of the Gods is to: 1) present his setup, 2) critique his evolutionary mechanism, 3) consider an alternate mechanism for how psychedelics led to the emergence of human consciousness.

PART 1:

The Food of the Gods Grows in Cowshit

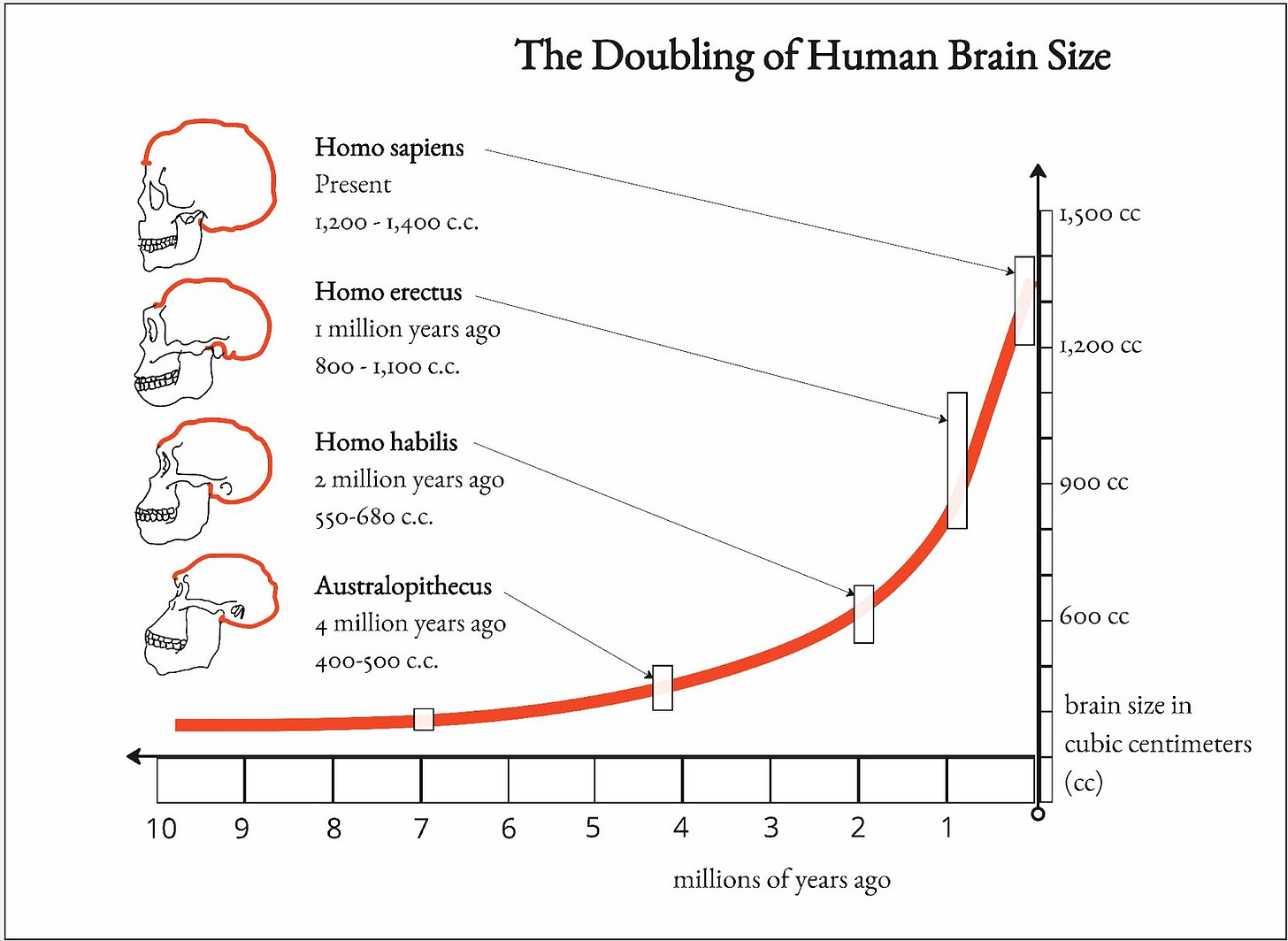

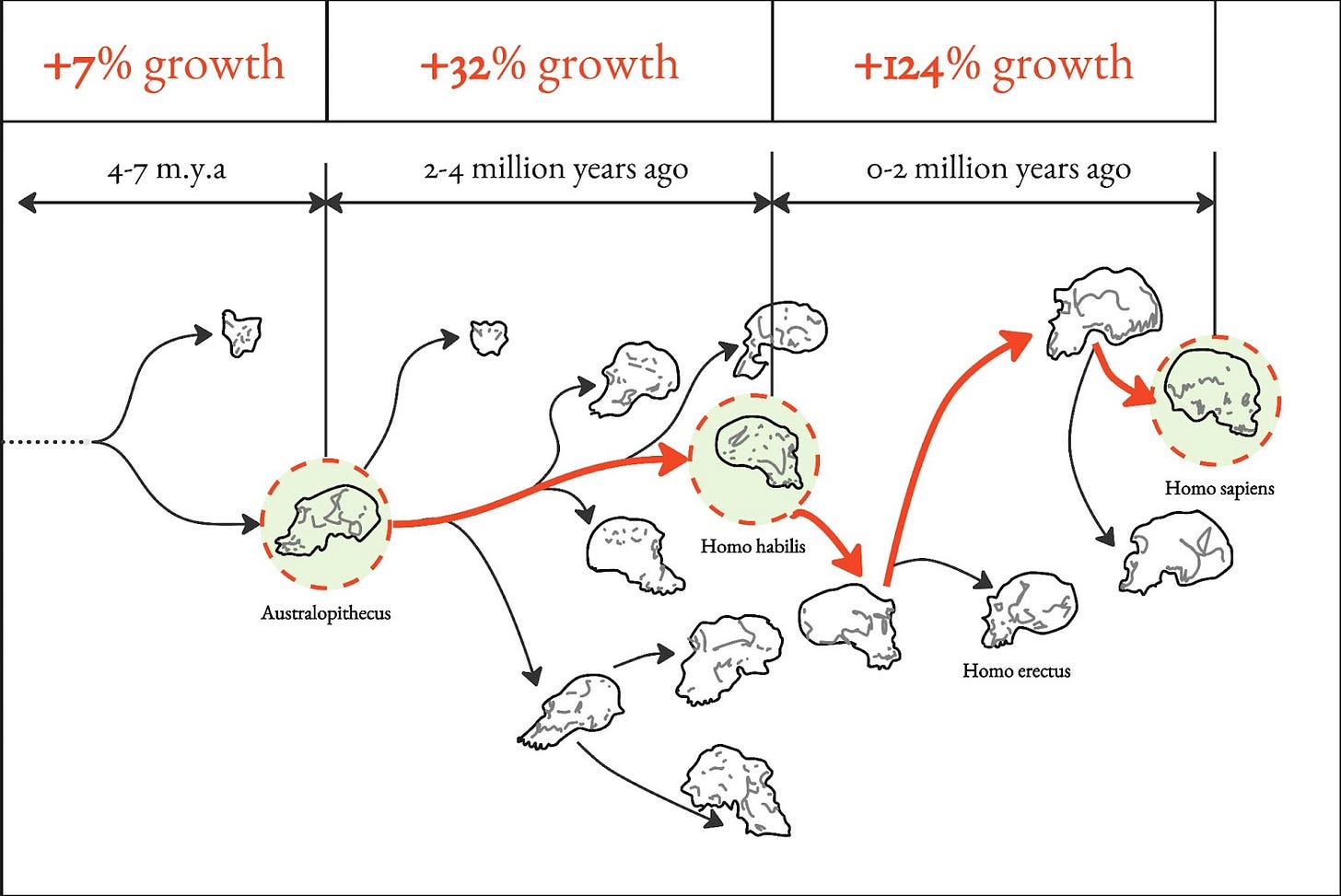

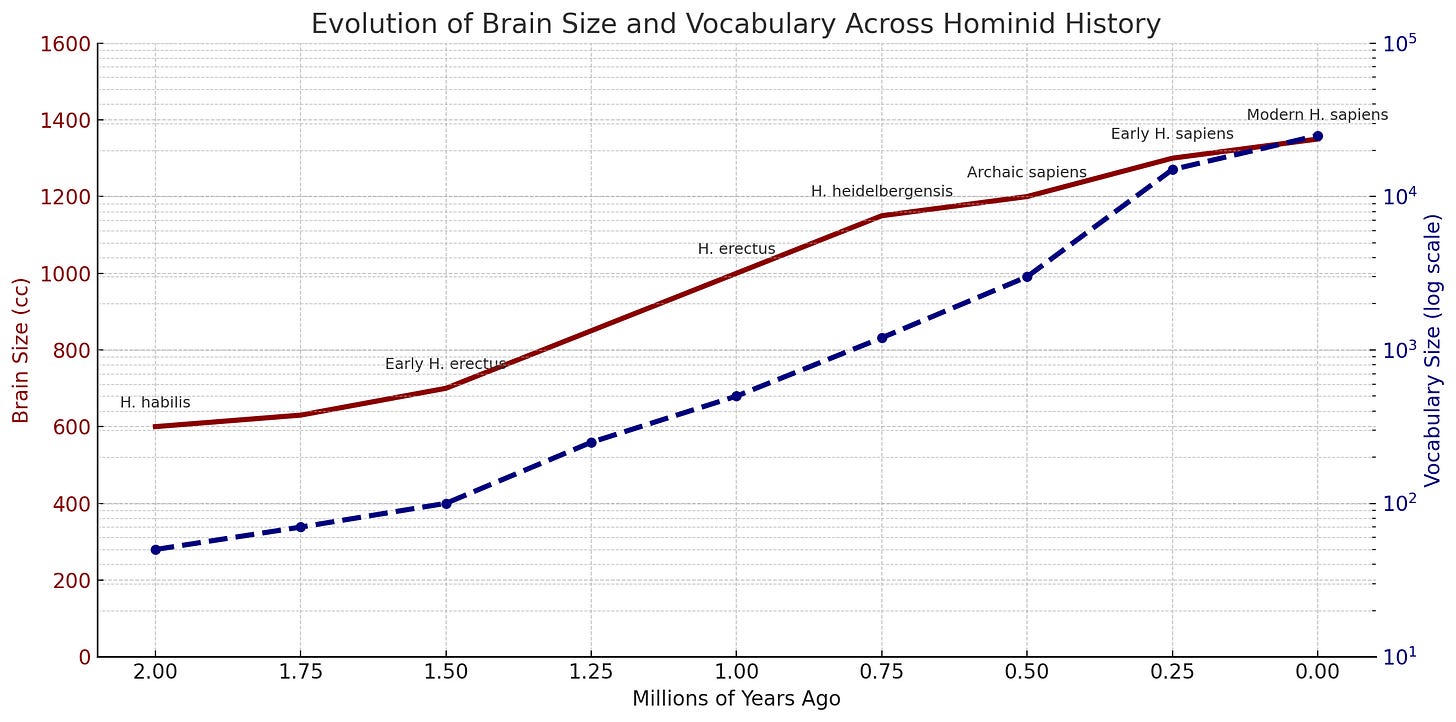

Terence McKenna’s hypothesis is a response to one of the biggest mysteries in human evolution: how did the brain size of the Homo genus double in only 2 million years?

For context, he states that “evolution in high animals … operate[s] in time spans of … tens of millions of years” (p.20). From 4-7 million years ago, the brain only grew around 7%. Then, from 2-4 million years ago, it jumped to 32%. Since Homo habilis emerged, our average brain size has grown 124%. Why the “sudden and mysterious expansion?” (p.22)

McKenna cites Lumsden and Wilson (authors of Genes, Mind, and Culture from 1981), who call this “perhaps the fastest advance recorded for any complex organ in the whole history of life” (p.24). Even the first chapter of Sapiens—the pop anthropology book by Yuval Noah Harrari—addresses this mystery: “What then drove forward the evolution of the massive human brain during those 2 million years? Frankly, we don’t know.” (Sapiens, p.9)

While we don't know exactly what sparked this growth, most theories point back to an extreme moment of climate change.

Between 2-8 million years ago, there were several periods of glaciation across the Northern Hemisphere. Expansive sheets of ice caused the air to cool and dry, reducing rainfall in the South. Rain forests receded and hominids were pushed out of their habitat and into the grasslands and savannahs that were emerging across Africa. This is called the “Savannah Hypothesis,” and McKenna alludes to it as he frames his theory.

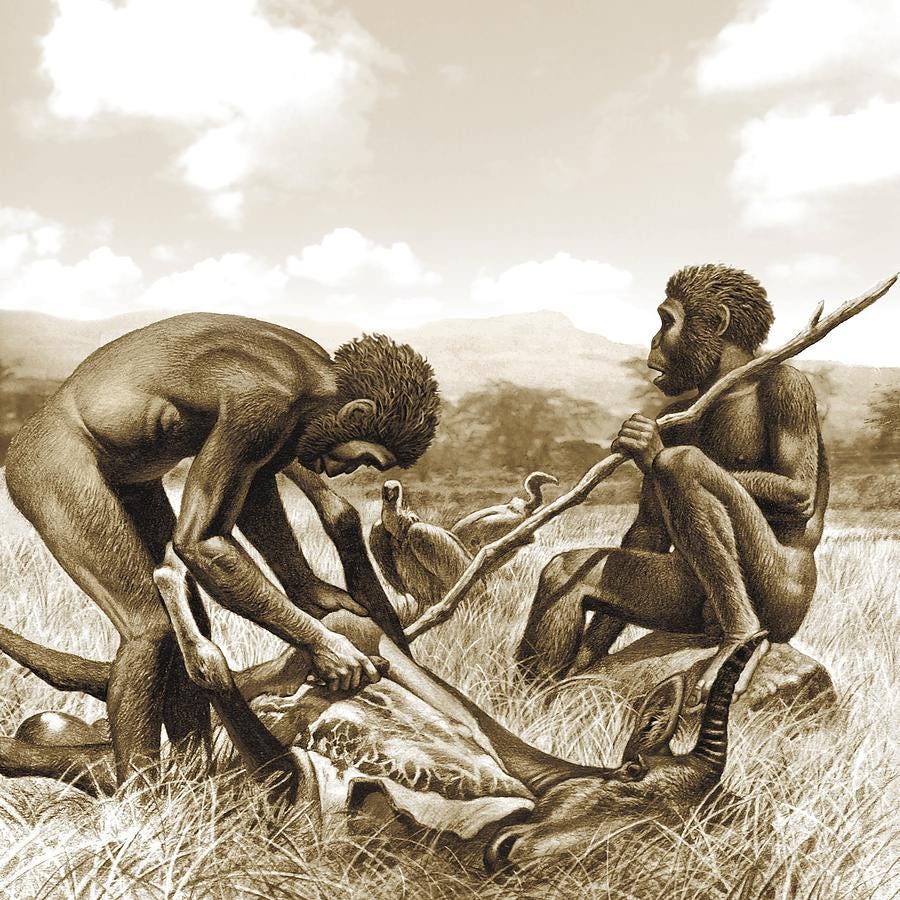

Every theory on how the human brain evolved is some kind of adaptation to the grassland. We relied more and more on bipedalism to navigate an open plain, which freed our hands to carry food, build tools, throw spears, and upgrade our thumbs. These tools—paired with social coordination—let small packs hunt bigger and bigger mammals, which required the invention of fire to eat meat, which led to more calorie-dense and nutrient-rich food.

According to McKenna, there’s another big factor in the grasslands that no one accounted for:

“Grasslands have far fewer plant species than forests. Because of this scarcity, it is highly likely that [an omnivorous] hominid would test any grassland plant encountered for its food potential” (p.35) [...] When our remote ancestors moved out of the trees and onto the grasslands, they increasingly encountered hooved beasts [along with] the manure of these same wild cattle and the mushrooms that grow in it.” (p. 37)

McKenna points to a blindspot in evolutionary theory: among all the other forces on the African plains were little mushrooms that accidentally led to synesthesia, self-reflection, abstract thinking, symbolic communication, and divergent problem solving. Yes, our brains also probably grew from bipedal tool-enabled meat hunting, but the road to survival was lined with mutagens.

According to Terence, “ human emergence … is a you-are-what-you-eat story,” (p.16) and it isn’t just meat. After a species moves into a new environment, its diet is in question and they’re desperate to experiment. “The strategy of the early hominid omnivores was to eat everything that seemed foodlike and to vomit whatever was unpalatable” (p.17).

Psilocybin cubensis is a species of mushroom that grows in the dung of not just cattle or bovines, but all herbivores. A new 2024 study dates Psilocybe back to 60-65 million years ago (around the time when the dinosaur-ending asteroid hit). They are pre-hominid. The wind spreads spores over fields, dropping them in hot, damp, nutrient-filled cow dung—the perfect microclimate for fungus growth.

It’s entirely possible that Homo habilis had psychedelic experiences, but how readily available were mushrooms in Africa 2 millions years ago? If mushrooms were the catalyst of the brain boom, then they must have been everywhere, right? Unfortunately we have no way to measure this, and McKenna doesn’t estimate volume, but we can at least anchor our speculations in the gross volume of cowshit.

Hypothetical: 10 million African herbivores, dumping 10 dung per day, leaves us with 100 million patties per day (incredible). Maybe 1 in 3 patties grow mushrooms, but not all of those mushrooms are psychoactive. If 1 in 10,000 patties are magic, then that’s something like 10k shrooms per day, or 3.65 million per year. According to a study by Navarette (2016), there were 18,500 members of Homo habilis at this time—meaning, 197 maximum trips per person per year. Of course, most of these were probably left to rot, but given the abundance, it’s not unrealistic to imagine 5-10% of Apes got stoned in a given year. (According to this psychiatry study, 7.1% of adults tried a psychedelic in 2022. Some things never change.)

Anyway, McKenna was the first to propose a human/cattle/mushroom symbiosis as an answer to the mysterious surge in brain size. Since the 1960s, others have speculated on the role of psychedelics in human evolution—apparently, Francis Crick, discoverer of the double-helix DNA spiral, was the first (!?)—but McKenna was an ethnobotanist who could refine the details and pitch the premise.

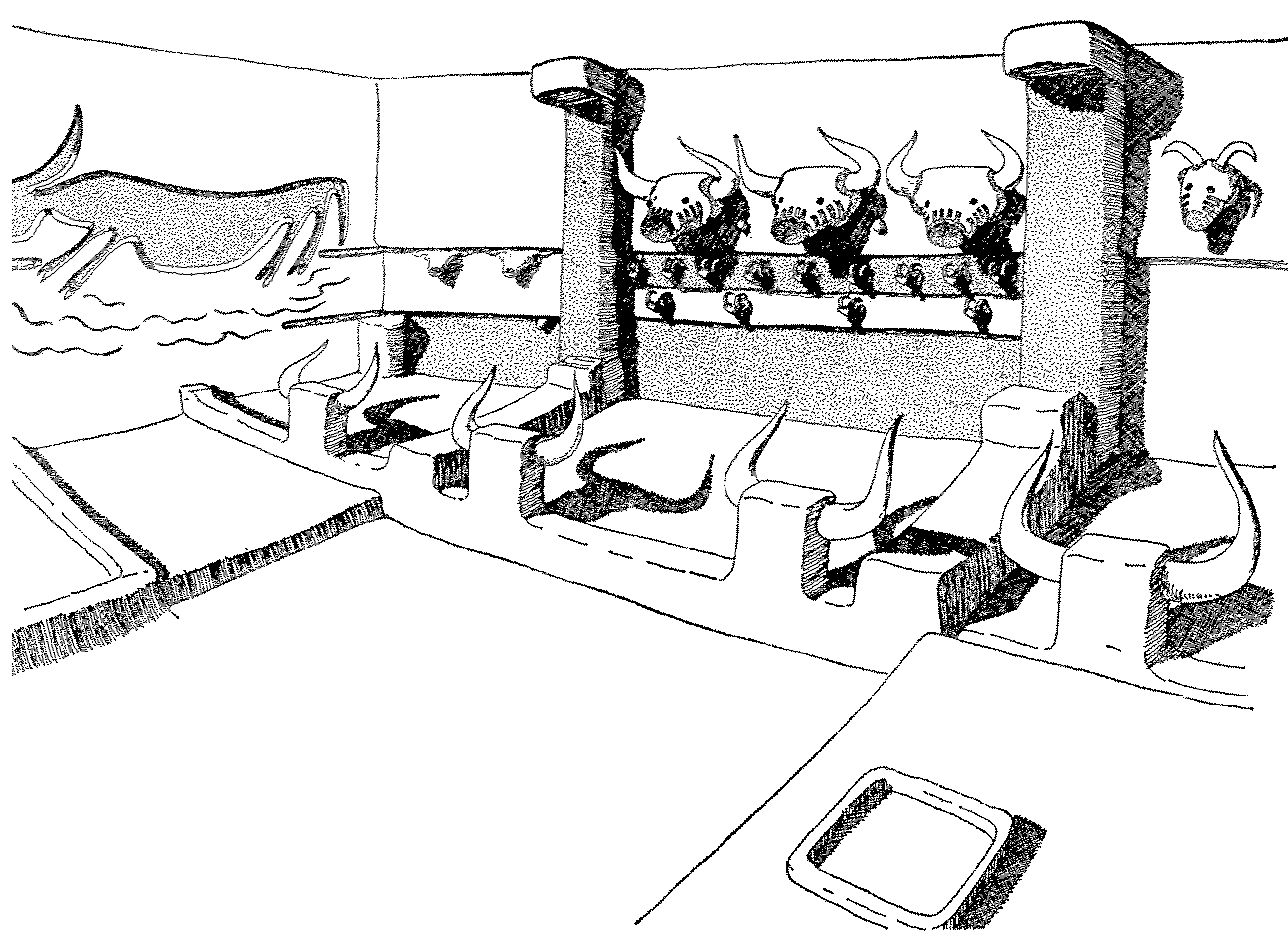

According to Terence, we used mushrooms to “bootstrap to higher and higher cultural levels” (p.39), and it’s not a coincidence that our earliest Neolithic religions (10,000 BC) worshipped cows. He shows us Sahara Desert cave art that features “shamans with large numbers of grazing cattle … dancing with fists full of mushrooms” (p.70). Then we see Catal Huyuk, “a huge [9th millennia BC] settlement, spreading over 32 acres … accommodating over 7,000 people”; the excavation revealed “amazing shrines with cattle bas-reliefs and heads of now extinct aurochs” (p.82). This proto-culture eventually shifted into the soma-fueled Vedic religions of India, where some of the Gods were actually cows.

McKenna, in his typical interdisciplinary fashion, pulls threads from anthropology, mycology, and comparative religion to make a compelling case: during an important moment for the Homo genus, we were in the presence of consciousness expanders. The food of the Gods was in the humblest of places. Great premise. The problem is, the proposed evolutionary mechanism is mostly bullshit.

PART 2:

Binoculars, Orgies, and Language

So let’s assume that proto-humans had access to some quantity of psychedelics for the last 2 million years. Wouldn’t these hominids get high, come down, and be biologically identical? Even if mushrooms promote neurogenesis, the effects aren’t inheritable. In fact, the whole idea that LSD “may alter the chromosomes” was a media-fueled cultural hysteria in 1967 that had to be debunked. If mushroom experiences don’t pass down to your offspring, then how could they have guided evolution?

McKenna has a 3-point theory on how the hominids who ate mushrooms outbred the others; this framework shows McKenna’s strength as a meme-maker. His section header is titled: “THREE BIG STEPS FOR THE HUMAN RACE.” It’s a triad—a 3-step explanation—forged in a way to be memorable, repeatable, and spreadable. This is exactly what happened.

To summarize:

In low doses, it sharpens your vision into “chemical binoculars” to make you a better hunter.

In medium doses, it makes you horny and more likely to reproduce.

In high doses, it leads to mystical experiences, problem solving, and language.

The framework is an anthropological cartoon, where the tribes who ate mushrooms were better hunters, better bonkers, and better thinkers, giving them a chemical advantage.

“In such a situation, the outbreeding (or decline) of non-psilocybin-using groups would be a natural consequence.” (p.25-26)

McKenna softens his theory by framing it as a “constructed fantasy,” but then analytically explains how the three forces are “interconnected and mutually reinforcing” (p.25). The framework is a solid meme—it’s simple enough to remember and riff to your friends; but when you investigate each point, it falls apart.

Low doses:

Microdosing as “chemical binoculars” for hunting

The first part of McKenna’s theory comes from a research study done by Roland Fischer in the late 1960s:

“[He] gave small amounts of psilocybin to graduate students and then measured their ability to detect the moment when previously parallel lines became skewed. He found that performance ability on this particular task was actually improved after small doses of psilocybin” (p.24).

Fischer’s study is proof to McKenna that a drug can give you a better model of the world. In terms of evolution, he notes how this chemical mutagen gave hunters an adaptive advantage, and it became “deeply scripted into the behavior and… genome of some individuals” (p. 25):

“... small amounts of psilocybin, consumed with no awareness of its psychoactivity while in the general act of browsing for food … impart a noticeable increase in visual acuity, especially edge detection. As visual acuity is at a premium among hunter-gatherers, the discovery of the equivalent ‘chemical binoculars’ could not fail to have had an impact…” (p.25)

“Chemical binoculars” is a remarkable coined phrase, but he’s vague in how a microdose can lead to a fork in the species, and worse, he’s way off on his source.

The Roland Fisher study used psilocybin in medium-high doses (160 µg/kg), not low doses (12 µg/kg). It also wasn’t about “edge detection,” but “visual acuity,” and the idea that a faster refresh-rate automatically leads to better hunting is an assumption that ignores the strong body load that occurs on mid/high doses. In fact, Fischer’s paper even says that psilocybin “may not be conducive to the survival of the organism” (the exact opposite conclusion that McKenna draws from the same study). Quite the skew.

Medium doses:

Arousal, orgies, and growing tribes

So not only are the microdosing hunters gathering more food, but at medium doses they’re having more kids.

“Because psilocybin is a stimulant of the central nervous system, when taken in slightly larger doses, it tends to trigger restlessness and sexual arousal. Thus, at this second level of usage, by increasing instances of copulation, the mushrooms directly favored human reproduction” (p.26).

And it’s not just an increased amount of sex as we know it, but medium/high doses change the nature of relationships, sex, and parenting:

“The boundary-dissolving qualities of shamanic ecstasy predispose hallucinogen-using tribal groups to community bonding and to group sexual activities, which promote gene mixing, higher birth rates, and a communal sense of responsibility for the group offspring.”

Does more reproduction automatically benefit the tribe and enhance the continuation of their gene pool?

If mushrooms led to orgies and population spikes, that could be a liability for a hunter-gatherer tribe. It’s more likely that a stable population size in Ancient Africa would have been ideal for survival. On page 19, he notes that if a species integrates sweet potatoes of the genus Dioscorea (the raw material we use for birth control pills) they would find themselves in a diet-induced reproductive chaos. The opposite could be equally true: a mutagen that leads to uncontrolled tribe growth would put a strain on already limited resources.

High doses:

God and language

And now, finally, at the highest, heroic doses of mushrooms, McKenna explains two types of effects: mystical experiences and the advent of language:

“Certainly at the third and highest level of usage, religious concerns would be at the forefront of the tribe’s consciousness, simply because of the power and strangeness of the experience itself. This third level, then, is the level of the full-blown shamanic ecstasy.” (p.26)

While much of the book unpacks the implications of mushrooms spawning religion, there are fewer mentions about how mushrooms could have been a catalyst for language, sparking an adaptive advantage. Here’s the clearest one:

“Psilocybin’s main synergistic effect seems ultimately to be in the domain of language. It excites vocalization; it empowers articulation; it transmutes language into something that is visibly beheld. It could have had an impact on the sudden emergence of consciousness and language use in early humans. We literally may have eaten our way to higher consciousness. In this context it is important to note that the most powerful mutagens in the natural environment occur in molds and fungi. Mushrooms and cereal grains infected by molds may have had a major influence on animal species, including primates, evolving in the grasslands.” (p. 42)

Out of his three points, the idea of mushrooms catalyzing language is the most convincing, but still, McKenna’s case isn’t very rigorous. This is the degree of his supporting material (with no footnotes or citations):

“Researchers familiar with the territory agree that psilocybin has a profoundly catalytic effect on the linguistic impulse” (p. 53).

Natural selection?

Right after he explains his 3-point theory, he shifts to address objections from Darwinists. He acknowledges that his theory sounds “smack of Lamarckism.” Jean-Baptiste Lamarck was the first person to develop a full theory of evolution (1802). He held the reigning theory until Darwin’s Origin of Species (1859), and is known for being wrong on his theory of “soft inheritance” (that changes to your body or mind within your life can be passed down to your offspring).

“While the mushrooms may have given us better eyesight, sex, and language when eaten, how did these enhancements get into the human genome and become innately human?” (p.27)

McKenna’s whole theory hinges on a good answer to this question, and unfortunately he fumbles it. In a dense 200-word explanation, he implies that language, vocabulary, and memory offered such a radical survival advantage that it created an eat-mushrooms-or-die situation. He’s saying that speech-like behavior “spread through populations along with the genes that reinforce them” (p. 28).

This is a weak attempt to make his theory seem Darwinian. The basics of natural selection say that, over generations, certain gene-environment combinations give members of a subspecies a survival and reproductive advantage; those without the right traits die out, and so the population fills with those who have it.

In order for the psychedelic experience to have altered the path of evolution from Homo habilis to Homo sapiens, via natural selection, three things must have been true:

Due to location, only a subset of the population got access to the mushrooms.

Among those who ate them, only some percent of users had (unspecified) "language genes" that enabled them to better conceptualize and vocalize their intentions.

The ability to wield language had such a significant survival advantage, that anyone who couldn't talk got outbred.

This is shaky, not just because there’s no detail on how genetic variance causes some to burst into language and not others, but mostly because it makes little sense how a few extra words would put another tribe out of existence. Sure, I’d imagine a Homo erectus tribe of 1,000+ words with advanced grammar could out-smart and out-hunt a nearby Homo habilis tribe with only 50 words. But the accumulation of language likely happened extremely slowly; based on the rate of vocabulary growth, we’re talking 1-5 words per millennia. Humans weren’t just competing against each other, but lions. Lions don’t play in the realm of words. So even if mushrooms enabled a genetically-blessed subspecies of Homo habilis to invent a few new phrases, McKenna isn’t making a good case for how this threatens the existence of non-psychedelic tribes.

Basically, all three points of McKenna’s framework—vision, sex, and language—are cartoon mechanisms for evolution. It’s totally possible that 2 millions years ago, hominids were surrounded by fields of mushrooms and had profound psychedelic experiences, but there’s still no real explanation for how it catalyzed humanity and fostered the explosion in our brain size, structure, and function. Based on what’s presented in Food of the Gods, it’s not clear how mushrooms are a factor in evolution at all, let alone the main factor.

PART 3:

Psychedelic Propaganda

Food of the Gods makes more sense when you understand the climate it was written in: a psychedelic blackout. In 1971 they were made illegal, and until 1995, the most qualified researchers in the world couldn’t touch them (after serious breakthroughs in the ‘50s and ‘60s). Now, it's obvious we’re in a “renaissance” with forward progress. But from ‘71-’95, there was no knowing if the situation would ever change. This led to an intellectual counter-movement, where whole books were written as a plea for legalization (their argument generally goes: “Look! Psychedelics have historical precedent in cultures, X, Y, and Z, and so therefore we have no right to keep these sacred plants illegal.”

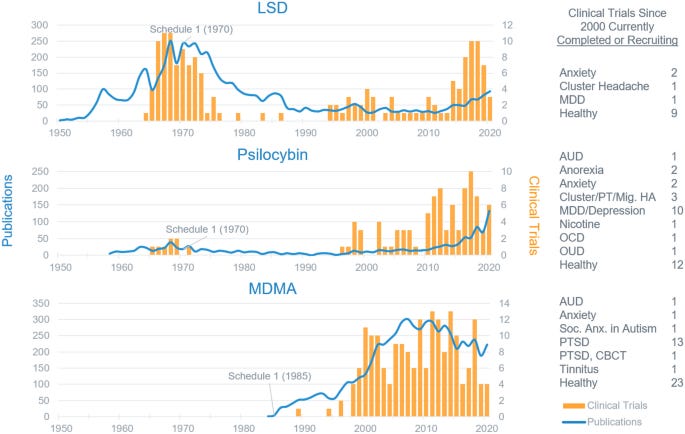

Look at 1992 (the year Food of the Gods was published): publications on psychedelics were at an all-time low (since their rediscovery in the 20th century), and 0 clinical trials were conducted with LSD or psilocybin. It was bleak.

Almost as soon as McKenna introduces the Stoned Ape theory, he moves on. The meme was planted, and rigor doesn’t matter. From page 57 on, we’re in the territory of his psychedelic manifesto which I can summarize in 3 points:

Chapter 5: Agriculture is the fall from Eden into history, ruled by a “dominator culture” of “pathological monotheism” (p.64). He makes a Learian plea for an Archaic Revival: “a clarion call to recover our birthright … It is a call to realize that life lived in the absence of the psychedelic experience upon which primordial shamanism is based is life trivialized, life denied, life enslaved to the ego and its fear of dissolution in the mysterious matrix of feeling that is all around us. It is in the Archaic Revival that our transcendence of the historical dilemma actually lies.” (p.252)

Chapter 6-14: Our substance addictions stems from an “existential incompleteness” from losing touch with the mushroom. He covers the history of drugs, from prehistory through the 20th century. He gives a literally exhaustive survey of mushrooms, ergot, cannabis, hashish, sugar, coffee, tea, chocolate, tobacco, LSD, cocaine, heroin, DMT, and television.

Chapter 15: The last page of the book is a 10-point drug policy, showing the real intention of this whole effort: activism. He covers taxes, the IMF, cartel laws, research, and education.

Here are two more quotes from Goodreads on how the messianic mushroomism gets tiresome:

“You can like mushrooms without believing they are the cause of all human innovation, religion, and culture."

“The contortion of historical evidence to make the mushroom the [center] of human evolution, societal development and ultimately suggesting we should all go back to its regular consumption eventually became ridiculous.”

You might not be surprised to learn that Terence McKenna confessed to having little concern for academic accuracy. Here’s a quote from one of his lectures:

“Since I feel pretty much around friends and fringies here, it doesn’t trouble me to confess … Food of the Gods, I conceived of as an intellectual Trojan horse. Written as though it were a scientific study, citations to impossible-to-find books and so forth … simply to ‘assuage’ academic anthropologists. The idea is – to leave this thing on their doorstep; rather like an abandoned baby, or Trojan horse.”

This pissed off a lot of McKenna fans, and causes accusations ranging from him being a complete fraud to a mal-intended CIA agent. When asked about his book in this interview, he sees it as a catalyst in a larger culture war. He wanted the unjustly illegalized drugs to be situated in a human origins scenario. In the same way that Darwin’s theory reset the 19th century Victorian mind, he hoped that equating psychedelics with evolution would trigger a new openness to them. He wanted to make the switch from:

“ ‘Drugs are alien, invasive and distorting to human nature’ to:

‘Drugs are natural, ancient and responsible for human nature.’ ”

For what it’s worth, I don't think McKenna is a complete charlatan. I think he had an interesting hunch and acted on it, but in the act of crystallizing it into a book, he was less interested in careful analysis and more interested in using his position as a psychedelic guru to shift the culture. His target audience was “drug-friendly 18-25 year olds” who would spread the ideas into the mainstream.

“You've heard me talk about meme wars, and how, if we could have a level playing field, these ideas would do very well.”

PART 4:

The Babbling Idiot and the Tribe

Despite all the problems laid out above (bad research, bad arguments, questionable intentions), I still think he’s onto something: maybe psychedelics never got into the genome, but at a critical moment in our evolution, our pre-lingual ancestors moved into a new grassy environment, one filled with mushrooms that are now proven to activate the language-forming centers of our brain.

Since 2014, a new wave of university-backed studies have confirmed a lot McKenna’s intuitions: psilocybin aids in abstract thinking and symbolic communication; it reduces top-down control and fosters spontaneous language; it increases semantic association, expanding the repertoire of usable words, and even facilitates the creation of new ones. Damn. We can’t know exactly how mushrooms affect Homo habilis vs. Homo sapiens, but there’s reason to believe something happened.

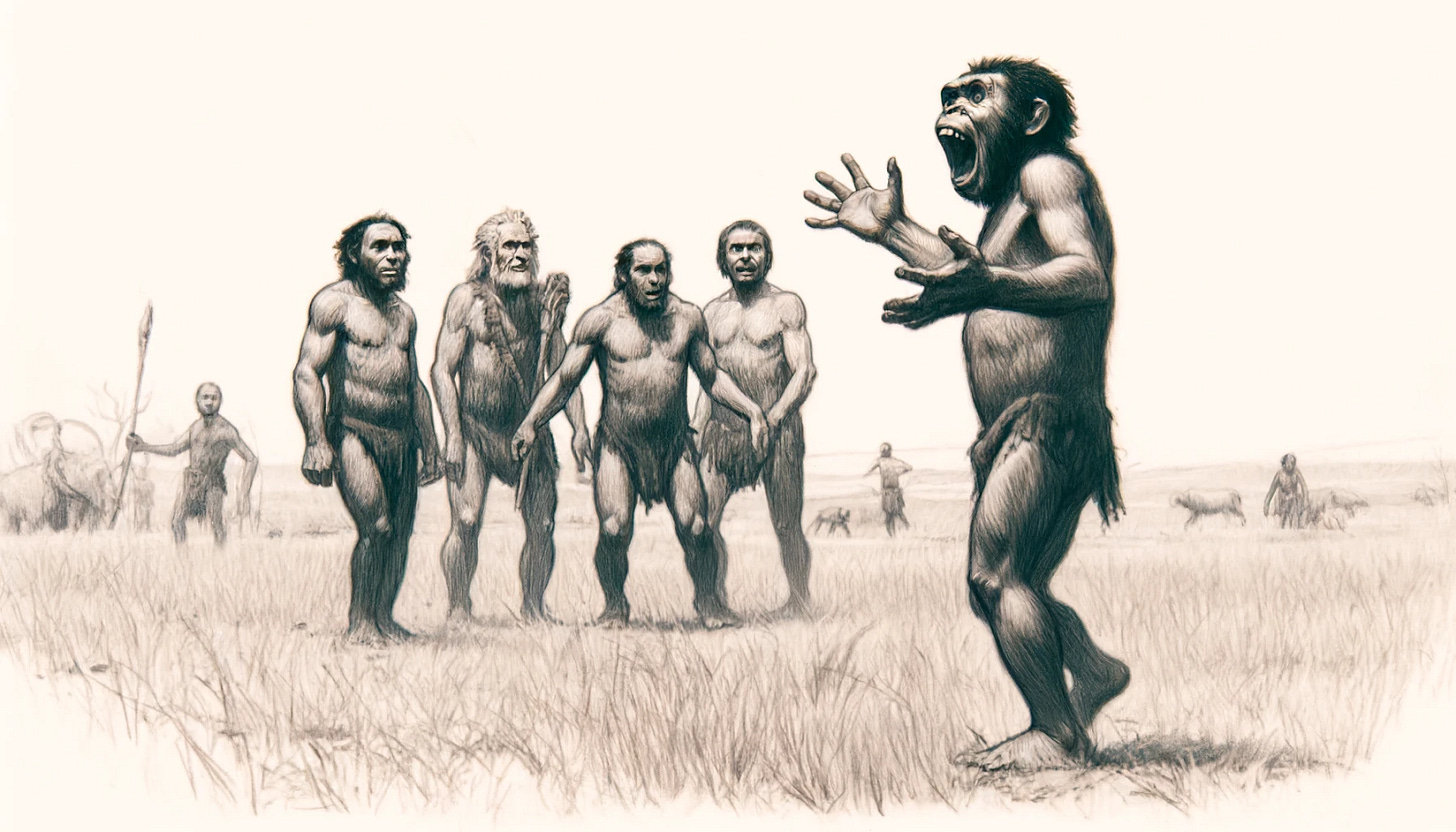

For one paragraph, I’d like you to entertain my own anthropological cartoon. It exists within McKenna’s premise, but without the glorification of the mushroom or the user. I call it: The Babbling Idiot & The Tribe.

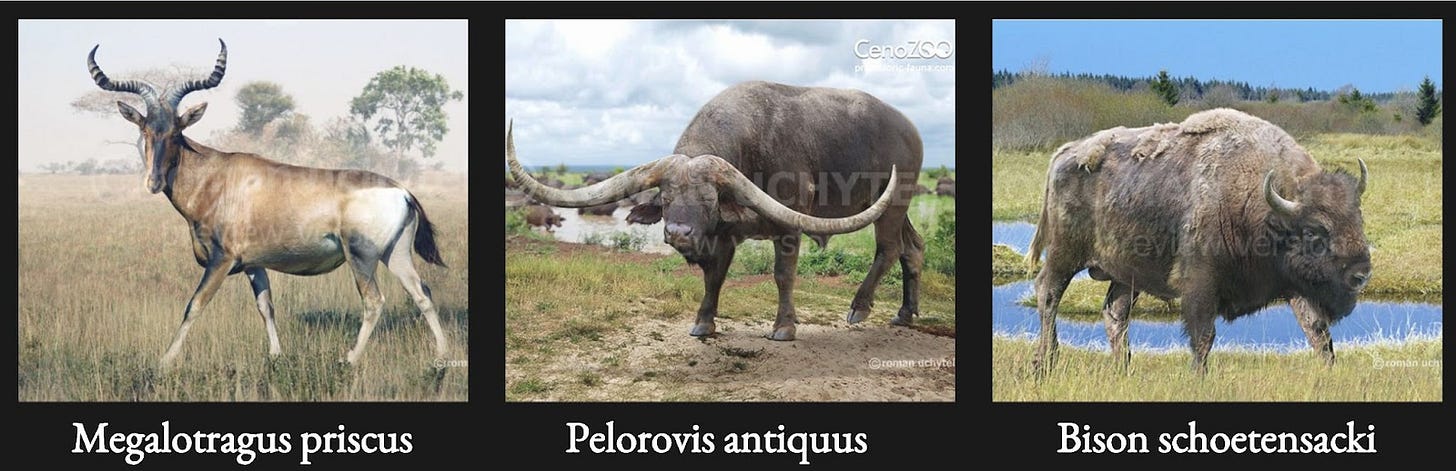

Imagine a hungry apex hunter stalking a Megalotragus, and in the process he comes across a dung patty that’s filled with a few mushrooms (appetizers). Unknowingly, he consumes a heroic dose of Psilocybin cubensis. An hour later, hunting is out of the question. There is slight nausea, a weirdness, and eventually, the spontaneous creation of mouth noises. As he comes back into contact with the tribe, he’s not just tripping, he’s grunting and riffing in ways they can’t understand. It’s frightening. From a state of synesthesia, the Babbling Idiot is attempting to make abstract connections between his intentions and his palette of possible sounds. You can imagine hundreds of proto-words coming through over the hours, none of them crystallizing into meaning. But in rare cases, perhaps aided by gestures, the tribe can grok what he means. Most of the words are forgotten, but some are coined in such a way that they’re useful and memorable. The babbling idiot was a temporary conduit for the logos, and came down with little to no memory of the ordeal. Sobered up, he hears a new word moving around the tribe, and asks, “what do you mean?”

This story inverts all of psychedelic romanticism that was baked into McKenna’s theory:

Mushroom use didn’t need to be frequent; this might have been a rare event.

The whole tribe didn’t need to take them; it could’ve been a single person.

It wasn’t brave or intentional; it could’ve been accidental.

They didn’t turn into a superhuman hunter, lover, or linguist; they became a babbling idiot.

They didn’t come down more evolved; they barely remembered it.

The hero isn’t the psychonaut; the hero is the sober tribe who paid attention through the chaos to catch and remember the words that mattered.

To bring this back to evolution, magic mushrooms may have simply been a catalyst for linguistic mutation. Over a tribe’s life, the lead hunters would accidentally get stoned a few times, and it would lead to outpourings of gibberish. In some cases it would threaten the survival of the tribe, in most cases it would have been kind of annoying, and in rare cases it would lead to the creation of a re-usable word.

McKenna was—literally—a remarkable babbler, and would even demonstrate it to his live audiences. He referred to it as “glossolalia,” the spontaneous urge to form speech on high-doses of psilocybin, despite it being void of meaning. It sounds eerie, almost like he’s speaking in tongues. This happened to him often enough that he started recording his outbursts on tape recorders. Now he can simulate it at will while completely sober. You can check out this 15-second version, or a longer version titled, “Recordings Which People Find Extremely Alarming.”

It’s not that psychedelics got into the genome, it’s that over many millennia they mutagenically expanded our repertoire of language.

The evolutionary mechanism here isn’t the mushroom, it’s language itself. Psychedelics can restructure your brain, but not your kid’s brain, and that’s okay, because the artifacts from a single trip are strong enough to infect everyone around you—even if they’re sober. Think of the words, music, art, culture, and technology that came out of the 1960s from a small subculture of trippers. Through mimesis, language ripples through cultures and generations like a shockwave. It’s time we consider that the word itself might have been the original burst from the mushroom.

Consider the power new words might have had on a Homo habilis with a vocabulary of less than 50 words. They had the linguistic range of a 2-year old, and used basic utterances and gestures for food, danger, and water. A million years later, Homo erectus, with brains almost double the size, had fire, technology, but also a modern vocal tract, with a vocabulary over 1,000 words, putting them at the fluency of a 3-4 year old. By the time Homo Sapiens were forging words in Egyptian cuneiform, their vocabularies were over 10,000 words.

The doubling of our brain size matches a logarithmic growth in our vocabulary, and so it brings us into a chicken-or-the-egg situation. Which guided which?

The natural assumption is that a growing brain breeds the hardware for language, but what if the opposite is also true? Over millennia, could increased vocabulary put pressure on the brain to grow? Could the two have existed in a feedback loop? Were ancient brains significantly smaller because of the absence of language? How does this relate to the critical window of language learning in children? If you were to time travel back 2 million years, kidnap a homind infant, bring them to 2025, and raise them like a typical child, how many words could they learn and how big might their brain grow? Might the mysterious doubling of our brains come down to a lineage of babbling idiots on mushrooms who slowly brought words to the tribe?

Answering these questions is beyond my expertise, and beyond the scope of a book review on Food of the Gods. But these musings have led me to the book I’ll read next: The Symbolic Species: The Co-evolution of Language and the Brain (1998), written by a different Terrence—Terrence Deacon (Amazon, Goodreads).

While Food of the Gods is dense, and the Stoned Ape Theory is flawed, McKenna’s meme is an outlier in that there’s actually more depth the further you look into it. After reading Terence, I’m more energized than ever to return to his lectures and engage with his exotic ideas. If McKenna is himself a babbling idiot at the frontiers of language, then we are the tribe tasked to listen carefully, forgivingly, and generatively—because the guy on mushrooms might be onto something.

Thanks for the feedback: Garrett Kincaid, Chris Coffman, James Taylor Foreman, Lily, Charlie D. Becker, Erin Nolan, Matthew Beebe, Becky Isjwara, Yehudis Milchtein, Chris Wong.

Thoughts? What’s convincing? What’s unanswered?

And now it's time for you to read Darwin's Pharmacy: Sex, Plants, and the Evolution of the Noosphere by Richard Doyle at Penn State...a book that so thoroughly and eloquently makes the case for "ecodelics" as "eloquence adjuncts" that contributed to the evolution of syntactic language, art, and religion under sexual selection for brain fitness that

1) I immediately befriended Doyle, who has become a priceless friend and mentor over the last ten years;

2) it became, in a glorious recursion of its own thesis, by far my most-recommended book; and

3) I suffered a "Where have you been all my life?" phase of intense frustration that it didn't exist ten years *sooner* when I was trying to pitch a PhD thesis on the mutually-reinforcing drivers of intelligence, social complexity, ecological complexity, language, culture, and behavior as the pattern underlying an emergent telos in evolutionary processes that could be generalized to the origin of life itself and used to predict our future relationship to technology.

Having a "NOW we can share EVERYTHING!" (Half Baked) moment right now but it may just be due to the fact I'm up at 5 am editing this damned essay for Aeon *again*...anyway, hope we talk soon and kudos to you for helping spread the gospel of tripping proto-humans.

Apropos of nothing here are a few conversations I've had on record with Doyle. He's a gem.

https://evolution.bandcamp.com/album/solpurpose-conversations-episode-2-richard-mobius-doyle (2013)

https://michaelgarfield.substack.com/176 (2021 also with Sophie Strand and Sam Gandy)

https://michaelgarfield.substack.com/h-01 (2024)

…i refuse to read this essay until you perform it in terrence mckenna drag…i need more meaningful elves in my life…