Every building has a site; it could be a dense metropolis, an AutoCAD strip mall, a sprawling suburb, or a somewhere in the sticks. The ultimate sin of architecture is when a designer ignores their context. My wife is an architect, and when we drive around Tudor-filled Queens and spot one of those McMansions trying to be an Italian villa—with plastic terracotta roofs and excessive Juliette balconies—she literally screams. It’s not just bad taste. The architect is so absorbed in their own design that they become blind to their surroundings. They forget to look up. Or worse, they choose not to.

Every idea has a neighborhood too, no matter how personal or original it is.

As an essay writer, your job extends beyond writing great sentences (voice) and putting them in the right order (form); you are also a cartographer of ideas: you sketch maps of your culture and put your story in context.

Your thesis becomes stronger when you frame it as a response to existing, related ideas. There are basically no rules on what you can respond to … it could be a manifesto by Sartre, Seth Godin’s glasses, the “duck architecture” in the show How I Met Your Mother, or Ron Weasley (ie: fiction counts; does it have name recognition among two or more people?).

Today’s post on Response is part of the Essay Architecture series; it’s one of three answers to the question: “what makes a great thesis?”

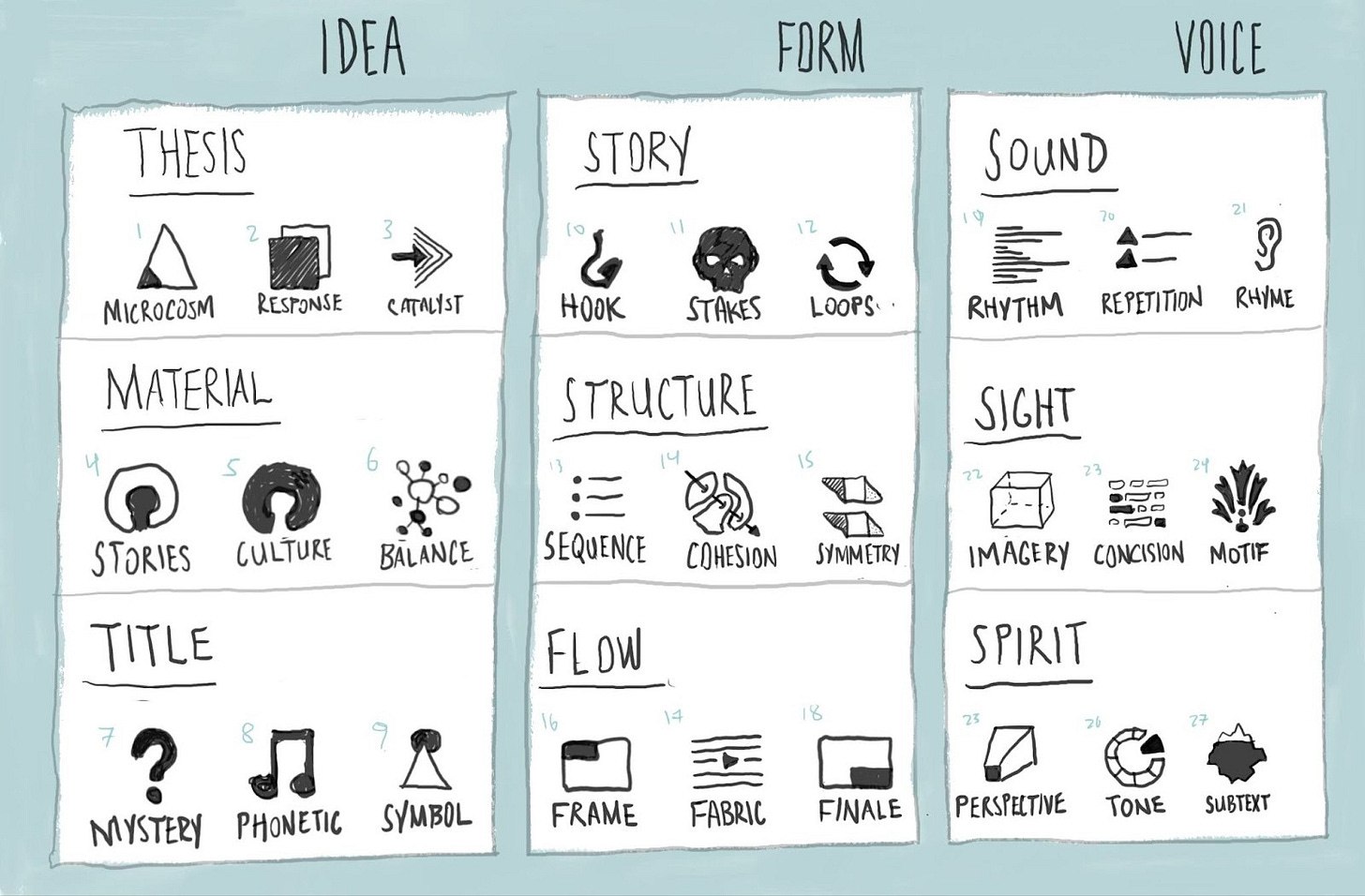

Recap: A THESIS is the singular anchor of your entire essay. It is a unique perspective, anchored in experience and culture, that organizes your stories, anecdotes, theories, and facts. There are 3 patterns in a great thesis:

MICROCOSM (paid post) is when a small frame reveals a larger truth. The frame can be anything: a volcano, a person, your friend’s engagement party, Super Bowl LVIII, a Mr. Rogers quote, Gollum, a lobster, a slug… When a tangible thing is framed to represent your thesis, your thesis becomes microcosmic.

RESPONSE: on building context around your thesis (today’s post).

CATALYST: on changing someone’s mind (coming next week).

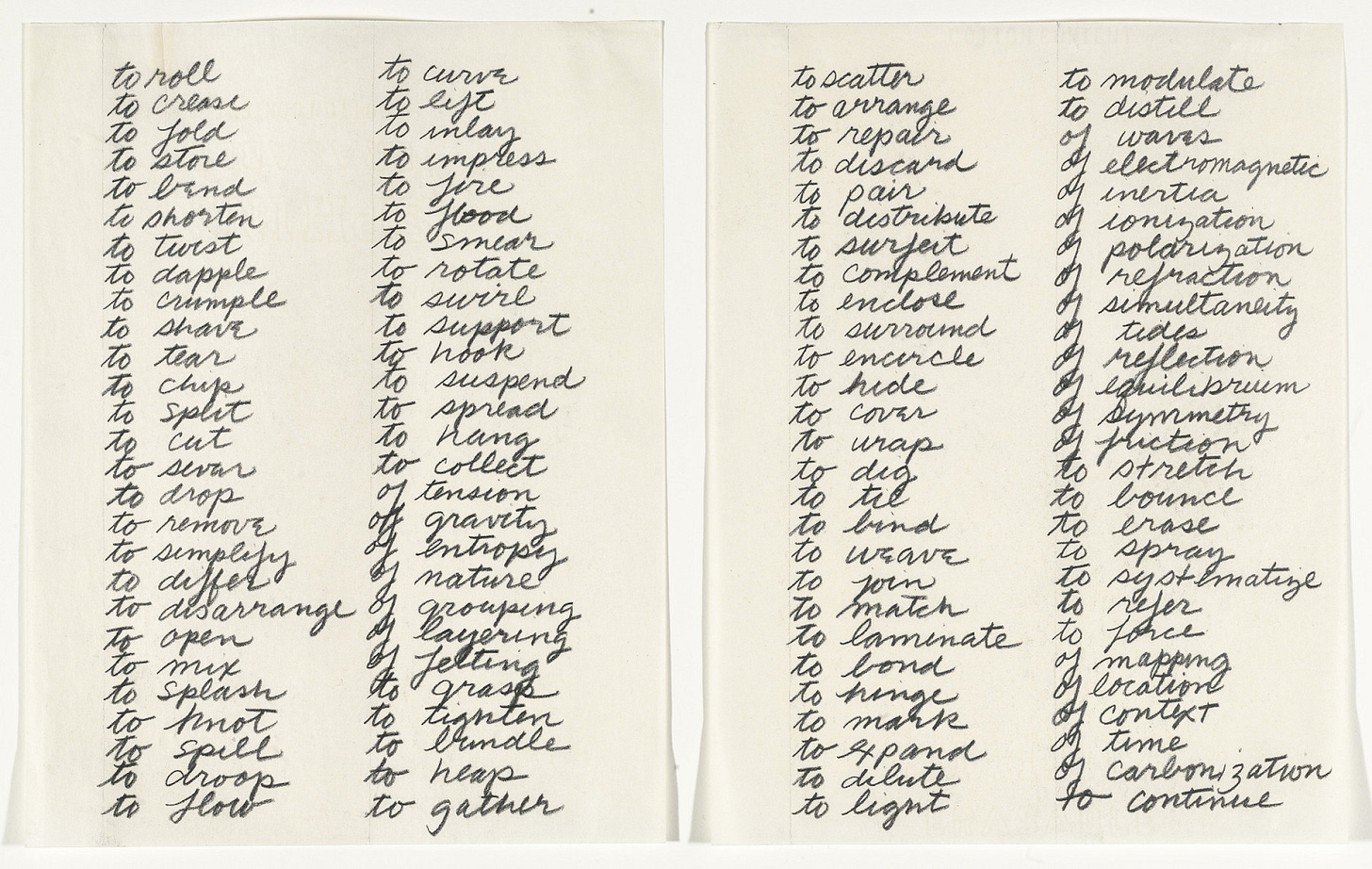

Since most of you reading this aren’t paid subscribers (yet) I wanted to share the main visual of today’s post. It’s inspired by Richard Serra’s 1967 “Verb List.” Serra was a modern, abstract sculptor, known for massive sheets of twisted metal.

You might not expect an organic sculptor to have a process that’s so anchored in language, but Serra’s list of 108 verbs is taught in art and architecture schools. It’s a dictionary of very specific ways you can alter an object: to droop, to knot, to smear … to dapple.

Our essays gain cultural richness when we frame them as responses, but we need a vocabulary that goes beyond “agree” and “disagree.” The image below shows different ways your thesis can respond (to extend, to contextualize, to codify, etc.). Later in this post, I’ll show how these 15 verbs can all branch from the same essay (in today’s case, “Why I am Christian again,” by James Taylor Foreman).

For $8.33/month, you’ll get essays like this all year that deconstruct the secret architecture of great essays. If you haven’t read it yet, check out the free chapter on Thesis.

Here’s a comment by David Kiferbaum from last chapter on Microcosm:

“This piece *immediately* unlocked something in a piece I was working on.”

Here’s a comment from Erin Nolan who just signed up for the Writer’s Studio:

“Michael has fundamentally changed the way I think about writing holistically, from first draft to final published essay. I come from a product design background, and his work helped me translate my design process to the process of writing great essays.”

Because I don’t promote the Writer’s Studio enough, I should make a quick note here: In addition to my chapters, the Founding Tier on my Substack ($300/year), gets a Calendly link to book live feedback sessions whenever and as often as they need them. It’s often 1:1 with me, and sometimes includes a small group. More details on that in this post (and feel free to DM me too).

If you don’t subscribe for either paid tier, I hope you still find value in the intro & diagram above. If you don’t wan’t my posts on the writing craft (free & paid), but still want my other posts (essays, updates, logs, etc.), you can update your account settings. Otherwise, hope you subscribe and enjoy the rest of this post.