How do you deconstruct prose?

Thinking in patterns without thinking like a machine. Of course Joan Didion uses repetition, but why?

Some books on ‘how to write’ will tell you that, to get good, you just need to reduce your favorite writers down to reusable formulas. This was the gist I got from Elements of Eloquence. There is a standard way people think about “rhetorical forms,” but it feels too convenient to dull down creative expression into a dictionary of mad libs. If you merely imitate the syntax of your favorite authors, you’re actually not so different from an LLM.

If you use flowery repetition because Joan Didion does, and you thought it was pretty, and it’s something you think good writers should do, but you don’t truly get when, why, or how to pull it off, you might sound more robotic than you think. It’s hard to differentiate AI writing from bad writing. They have the same problem: they replicate patterns without understanding them beyond the surface.

I bring this up because—now that I’m done with the lift of launching Essay Architecture (.com)—I’m resuming what is the infinite game of this project: reading and deconstructing great essays.1

Despite what anyone tells you—especially me—the simplest way to get good at writing essays, I think, is to read more “good” essays.2 Here’s a reading list of 100 I’ve put together.3 You really do gain a lot just from exposure, but once you get a habit going, it helps to consider how you read, too; the right analytical lens (along with deliberate practice) can unlock even more.

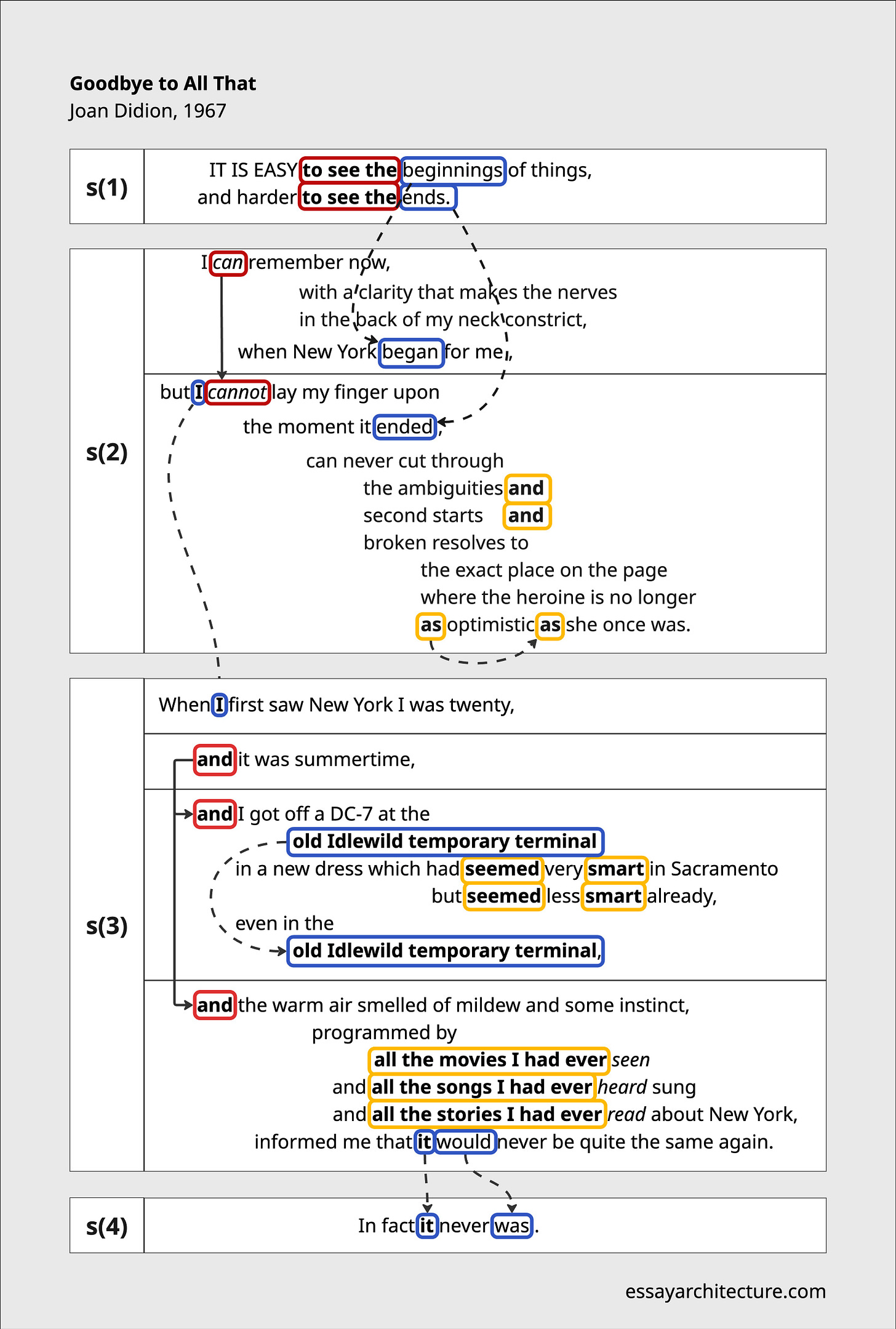

Let’s look at an excerpt, but we’ll go beyond “here are some repetition templates,” and into “in what situation would a writer do this?” Here’s the opening four lines of “Goodbye to All That,” a 1967 essay by Joan Didion.

“IT IS EASY to see the beginnings of things, and harder to see the ends. I can remember now, with a clarity that makes the nerves in the back of my neck constrict, when New York began for me, but I cannot lay my finger upon the moment it ended, can never cut through the ambiguities and second starts and broken resolves to the exact place on the page where the heroine is no longer as optimistic as she once was. When I first saw New York I was twenty, and it was summertime, and I got off a DC-7 at the old Idlewild temporary terminal in a new dress which had seemed very smart in Sacramento but seemed less smart already, even in the old Idlewild temporary terminal, and the warm air smelled of mildew and some instinct, programmed by all the movies I had ever seen and all the songs I had ever heard sung and all the stories I had ever read about New York, informed me that it would never be quite the same again. In fact it never was.”

This is the Hook, and hooks are hard4 because they have multiple jobs: they have to open a Tension, preview the Thesis, and establish the literary Tone. So naturally, a good hook often contains an insane density of patterns. There are 11 patterns in here, almost half the system,5 but I want to focus on the obvious one: Repetition.

I’m sure some of the loopage popped out to you, but the best way to deconstruct something is to visualize it. You only have so much bandwidth to make sense of a wall of text. By breaking sentences into vertical fragments, like a prose-poem, you see its modules. By spacing them with horizontal indents, you see how parts align, and how thought burrows inward. By overlaying shapes, lines, and colors, you comprehend the relationships almost instantly. When prose is in its natural form, the patterns are invisible; to understand something, restructure it so the patterns are obvious.

This is the practice of architectural diagramming,6 but applied to essays. Now read it again, and notice the nuances of repetition you might have missed before:

So, how do you absorb this? How would you learn to think and write like this if you want your own writing to have a similar quality? (I picked this example because it’s far too complicated to reduce to a simple equation.) It’s not about parroting rhetorical devices, but understanding how the devices help the writer articulate and augment what it is they’re trying to say.7

I love this example because it shows that repetition is more than a trick for whimsical prose-poetry, its structural rebar too. Without looping phrases to expose the logic of her lists, these elaborate ideas would collapse into complexity. A repeated phrase serves as a variable to connect two non-adjacent ideas. In sentence 2, when she says “I can,” goes on a riff, and then says “but I cannot,” you know what’s about to come will contrast what was just said. Sentence 3 is 98 words, 3x longer than her average sentence in this essay, but she uses an “and” stamp to divide it into three manageable ideas. And, in both s2 and s3, the subdivisions have their own nested repetition schemes! There are devices inside devices inside devices, all to the end of containing chaos.

If8 you find yourself in a situation where you find yourself needing to pack a significant amount of detail into a single sentence,9 then you might want to expose the structure of your ideas through repetition. This lets repetition work like a punctuation device, helping the reader get the relation between ideas in as compact a form as possible. Of these 184 words, 55 words are “looped” (30% of words repeat!). Repetition is not just a jewel, it’s a compression device. It lets you travel far without feeling tired.

There are many types10 of repetition, and also, many jobs of the pattern: to compare, to connect, to enumerate, to emphasize, to expose, to burrow, to anchor, to crown, etc.11 Within each of my 27 patterns is a whole universe of types, and the goal of my Essay Architecture book is to map everything as I read and deconstruct.

There are 2 different ways you can take part in this:

Free subscribers will keep getting posts like this. I’ll always include links to the original essay, along with at least one visualized example of a pattern, so you can both see it and understand why you would use it.

If you want to upgrade to a paid subscriber, you’ll be able to click into any of these pattern pages to find definitions, theory, exercises, rubrics, and a growing set of examples. From “Goodbye to All That,” I’ve already added 3 more visualized examples to the Repetition page (with more notes to upload). If you want to zoom out before committing, check out the Table of Contents, my primer on the system, or my free essay on the Voice dimension.

If you’re not interested in getting more deconstructions like this, but still want my other essays and updates, you can go to account settings and uncheck “Deconstructions.”

Footnotes:

Last year I did a few deconstructions, and wanted to link them here in case you missed them: How Tracy Austin Broke My Heart by DFW, Against Interpretation by Susan Sontag, and Here is New York by E.B. White. The last two took 50+ hours each, because my goal was to dissect each essay along every dimension. Now, I want to narrow the scope so I can get into a groove and do these more frequently. Each time, I’ll still focus on a single essay, but I’ll likely pick a single excerpt or pattern.

I’m often surprised when I talk to an aspiring essay writer who tells me that they read fiction and poetry and business books and self-help but not literary essays. It’s a genre! Imagine trying to write a book without having read one. If you are struggling with voice or structure, go read classic essays. Not only that, I suspect that reading old essays is the best way to get exposure to the extents of literature. You can read a “great work” in a single sitting, letting you cover ground faster. But more interestingly, essays are an “overflow medium,” meaning, as novelists and poets come up with ideas that don’t quite fit into their main medium, they capture it as an essay, almost accidentally, because essays are the way to capture your thoughts. Consider how Aldous Huxley is known for three books, but has written hundreds of essays. By reading essays, you enter a plenum that spans the world of literature.

Once this library grows to 1,000+ essays, I want to build out a a feature where my essay app recommends classics based on what you upload. The recommendations won’t be based on content similarity, but on your “composition profile.” For example, if a writer gets a 4.9 of 5 on Argument but a 1.2 on Rhyme, they might plea, “I’m not going for Rhyme, because fancy prose distracts from my point.” And so that’s when my app would be like, “Have you read G.K. Chesterton? He scores 5.0 on both.”

Joan Didion on Hooks:

“What’s so hard about that first sentence is that you’re stuck with it. Everything else is going to flow out of that sentence. And by the time you’ve laid down the first two sentences, your options are all gone.”

Re: the hook of “Goodbye to All That” — The first line has a clear, short, generalized Frame, and also, she outlines her Argument (on clear starts and fuzzy ends). The second one Flows into more specificity, with unique Word choices, multiple Rhymes, and a neat Perspective shift (referring to herself as a “heroine” in the third-person). The third sentence brings personal Experience and rich Imagery into a big sentence that resolve into a 5-word fourth sentence, creating an abrupt change in Rhythm with powerful Subtext.

When visualizing an essay, we take a linear 1D medium (prose) and make it a 2D image. Architecture is similar, but the opposite: 3D buildings have too much complexity, so to understand them we have to reduce them into analytical 2D plan diagrams.

In the flow of writing, I really do think you need to let the content organically pour out of you, with as little thought to patterns and devices as possible. All the analytical thinking should be siphoned off and done intensely when you read, study, and edit. You want to etch this stuff into you, so you can access it when you actually need it. This is why I’m trying to focus on the situation in which you might reach for a pattern.

This reminds me of a trick on how writers should study vocabulary differently. If you’re studying for the SAT, you memorize the word on the front of the flash card, because you want the word to trigger the correct definition so you can fill in the right bubble on your scantron. Writers should do the opposite. If you want to expand the vocabulary in your prose, you want the front of the flash card to show the definition. This way, as you’re trying to articulate a specific phenomenon, you’ll have more words to reach for. Thank Matt Švarcs Richardson for this one.

I‘ll add: if you understand the why behind a rhetorical device, you can eventually shed the device and invent your own. An artist is one who does not default back to their tried-and-proven tricks and templates; they continuously reach for fresh solutions to their problems at hand.

I wonder if all writing advice, and possibly all advice in general, should come in the form of if/then statements. It’s less mimetic, but if you don’t know the conditions in which advice applies, then isn’t it sort of useless? I said this on a podcast recently, and a commenter accused me of “promoting us all to think like machines,” not realizing that conditional logic goes back to ancient Greece.

An example of bad advice that ignores context is “don’t use long sentences.”

Around 2.5 years ago, I made a Twitter thread on 17 types of repetition in Vonnegut’s Cat’s Cradle (a friend asked me, “don’t you need to zoom out a little bit?” which may have prompted Essay Architecture to exist). Today’s post has brought me back to the sub-pattern scale of thinking. The difference is, now that I have a larger framework to assure me that I’m not getting lost in the weeds, I’m absolutely entering the weeds. How much deeper can these frameworks go? We already have dimensions > elements > patterns, which is a lot to chew on, but now each pattern apparently has it’s own hierarchy of parts too? Within repetition, there are syntax-based parts (“stamps” vs. “loops”) which then combine to create types, to serve particular roles—and maybe parts, types, and roles each have dictionaries of instances which can be grouped into categories—and you can quickly see how this spirals into a special kind of nomenclative hell. It is very tempting to just say “here are examples” and leave it at that. I’m sure I’ll find some middle ground.

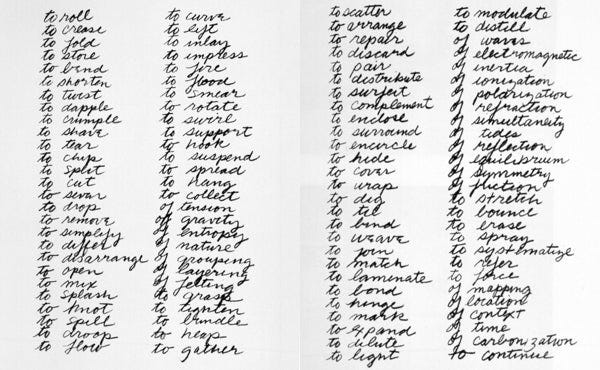

I’m inspired by Richard Serra’s—a sculptor’s—verb list, and I like the idea of classifying examples through actions that are easy to remember. I am making a conscious decision to stay away from the classical names for rhetorical devices: “anaphora,” “epizeuxis,” “polyptoton,” etc. 2 of these 3 three words are getting the red typo squiggly in the Substack editor because that’s how infrequently they’re used. Of course, all the phenomenon these Latin words describe are real, but they are as anti-mnemonic as it gets. If you’re trying to teach writers dozens of concepts, the last thing you want to do is give them multi-syllabic, pompous names. If you want these devices to be remembered and used, they should be named after common verbs, and should strive to be two-syllables or under. We have to start over. See Richard Serra:

Life Tip: Find someone who will love you like Michael Dean loves essay structure.

This is fantastic! Thank you. I laughed out loud reading "a special kind of nomenclative hell". Indeed.

I was especially intrigued by footnote #7 and #8 because I agree....let loose stream of consciousness writing to begin (and then again, often while working through revision analysis), because it is this, and I'd hazard only this approach (loose, dreamy, indulgent, playful, joyful...) can pull up/reveal the images and emotions and "thoughts we didn't know we thought" from deep subconscious. I'm only now beginning to understand how to work with this layer and move a piece through pattern analysis to make a work of at. Very very early stages...like, amoeba level arc of evolution. Sigh. Takes time. So, I'm always cautious of jumping to "if/then" algorithmic thinking in my writing...trying not to miss the wisdom poking it's head above the surface of subconscious to conscious...surfacing from deep dark waters to gulp the air of systematic analysis.

Again, thank you for this essay on repetition and diagramming thinking chunks ....hugely helpful!!!