Voice

Are you articulating your ideas so that your reader can feel, hear, and see what you mean?

A writer’s Voice is a literary texture that permeates every sentence. It is both an expression of personality and a love of language, making it the dimension that most shapes the reader’s experience.

There are thousands of decisions to make in the assembly of an essay; make them mindlessly and it will be littered with cliches and abstractions, but make them intentionally and the reader will be entranced by a unifying presence.

I know writers who only care about the rigor of their ideas, and think that patterns like Tone (7.1), Rhythm (8.2), Rhyme (8.3), and Imagery (9.1) are pretty tricks for writers, but not thinkers. But no one is above voice. We can’t forget that reading is an act of friction: it takes work to compile strings of words into meaning, and so every sentence is cognitive labor. To combat this, you want to hit your readers in their nervous system; just as important as what you say (logos) is how you say it (pathos). Both Susan Sontag and Joseph Conrad said the purpose of [voice] is to activate the senses: to make you feel, to make you hear, and above all, to make you see. Good prose turns language into a linguistic hallucination; it compels a reader to read thousands of words on any topic.

As the Internet gets crowded and AI advances, less writers will doubt the importance of voice; the real debate is on where voice comes from. Is it supernatural or can it be captured in a style guide? Is it artistic or engineered? Spontaneous or imitated? Does editing kill it or augment it? I don’t love these questions. I don’t even like the romantic idea that each writer has their own precious voice, a literary thumbprint waiting to be discovered, that unifies all their work with an iconic aura. Your voice should be constantly evolving with you, not frozen into a brand. It is too reductive to define voice with petty adjectives: “casual” or “funny” or “abrasive” or “self-conscious.” Instead, I think there are universal questions beneath all voices; our goal should be to learn those questions, and to continuously transform how we approach them.

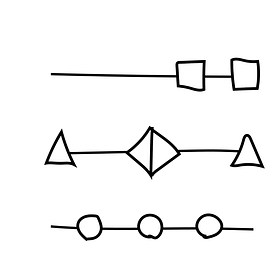

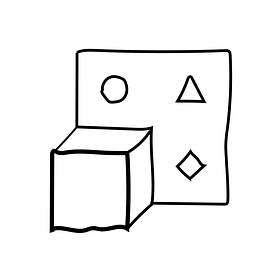

The most ethereal part of a writer’s voice is their Spirit (07) which covers their underlying attitude, their angle of vision, and the implications behind each sentence. I’m not saying that some vibes are better than others, but that there’s skill in dynamically adjusting your emotions to the Material at hand (otherwise, it is—definitionally—robotic). Then there is the element of Sound (08)—covering repetition, rhythm, and rhyme—which are patterns of syntax that are most noticeable when read out loud. They’re not just poetic, these patterns help you make associations, control pacing, and spotlight ideas. And finally, Sight (09) makes your writing concrete. The right words coalesce into pictures and make dancing images in the mind’s eye.

I think it’s possible to be both mystical and analytical about voice, but personally I think it’s hard to engineer a beautiful sentence; they usually come through accidentally. However, you can use analysis to figure out the dull patches of your draft, and keep riffing in those areas until something feels right.

Whether it comes out in a single huff or it takes rounds of toil, voice is the projection of an organic personality. This means that it’s sensitive, highly attuned to the material at hand. It’s not just the posturing of a literary style, but it’s a profound thoughtfulness around language, an ability to wield all of literature’s tools to put into words how you actually feel about the object in focus. Organic voice earns the trust of the reader, because they can immediately smell if you’re rehashing canned phrases to seem funny and deep, or if you’re actually inviting them into an approximation of your consciousness.

Upgrade to the $10/month tier to unlock all the element and pattern pages below.

Spirit (7)

Are you modulating tone, shifting angles, and concealing meaning so the reader infers what you mean without saying it?

Behind a writer’s prose is an intangible SPIRIT that permeates every sentence. Compared to the other elements of Voice, this is the one that is least computable through syntax. Your ...

Tone (7.1)

Do you shift between rhetorical modes to create a dynamic attitude?

TONE is the attitude implied through a writer’s choices in language. It’s tempting to label a writer’s Spirit (7) through single-word emotions (ie: “authoritative,” “snooty,” “aggressive”), but that would make for a one-dimensional voice. Instead, are there foundational qualities of tone that ...

Perspective (7.2)

Are you shifting between angles of delivery to create a layered presence?

PERSPECTIVE is the vantage point of a writer. While certain genres are anchored in a particular perspective—a memoir in the 1st-person, marketing in the 2nd-person, and journalism in the 3rd-person—an essay is the unification of all three. Through history, the essay has been conceived as ...

Subtext (7.3)

Do your sentences imply more than they say?

SUBTEXT is the implicit meaning behind each sentence. This pattern is often taught through “The Iceberg Principle,” suggesting that the majority of what you convey is subsurface, behind the page. By combining specific words in specific ways, you create ...

Sound (8)

Are you using musical prose to enhance the beauty and coherence of your ideas?

SOUND is the musicality of syntax. If you were to deflate words of all their meaning, you could still arrange gibberish into sublime rhythms. Your sentences need to shimmer, to oscillate, to fold back in on themselves. Of course, we’re not doing this for the sake of it; each sonic pattern also achieves ...

Repetition (8.1)

Are you deliberately looping words or phrases to expand ideas and create associations?

REPETITION is the act of intentionally looping specific words or phrases. Of course, not all repetition is good. If you accidentally make the same point twice in two different sentences, it’s redundant. Cut it. We’re talking about repetitive syntax: identical strings to emphasize, to expand, and to ...

Rhythm (8.2)

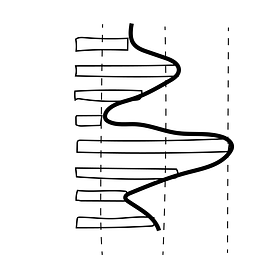

Do you shit between compression and expansion to control pacing and emphasis?

RHYTHM is the art of making your prose breathe. At the scale of words, sentences, and paragraphs, you want to break out of repetitive forms, and instead, dance between extremes. Run-on sentences are allowed. So are short ones. The most basic advice here is to "alternate between sentence lengths,” but rhythm ...

Rhyme (8.3)

Do you use lyrical devices to activate the ear and elevate specific phrases?

RHYME is the phonetic resonance between two nearby words. In addition to standard rhyme (matching end syllables) and alliteration (matching front syllables), prose writing is more concerned with assonance (vowels) and consonance (consonants). Unlike poems, essays don’t have rigid stanzas with explicit rhyme schemes; instead, you want to ...

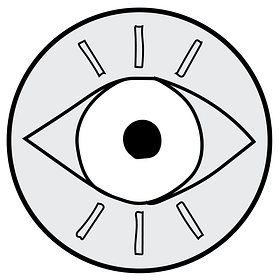

Sight (9)

Are you selecting specific words and concrete images to make your writing tangible and symbolic?

SIGHT is about creating a stream of words and images that enable the reader to see what you mean. It is our primary sense. We say a picture is worth a thousand words, but our challenge as writers is visual compression: to create the most vivid images in the least amount of ...

Imagery (9.1)

Do you use vivid and figurative prose to show what you mean?

IMAGERY is the cascade of mental pictures created in the reader's mind through descriptive language. There are three ways to make your essays more concrete: Sensory details show the qualities of an object (through ...

Words (9.2)

Are you creating a concise fabric of words so that precise, inventive ones stand out?

WORDS are the building blocks of prose, perhaps the most granular unit of literary composition. The process of selecting the right word from a dictionary of words is called “diction.” In different contexts, you may veer towards ...

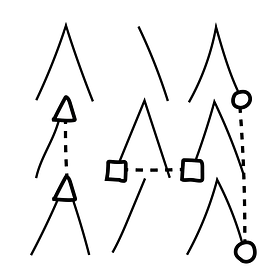

Motif (9.3)

Is there a recurring symbol that reloads meaning through the essay?

A MOTIF is an image or imagistic theme that recurs through the essay. It can be a concrete object, an extended analogy, a cultural reference, a quote. Whatever it is, it evolves a simple object into a symbolic anchor. Each time a motif occurs, it ...