Idea

Have you explored a terrain of concepts to find a central idea that can organize complexity?

An essay is consciousness frozen in words; it is an artifact that captures the thoughts, feelings, and events that transpire as you explore and makes sense of an Idea you care about. There are no rules or limits on what’s worth writing. An idea can be driven by a question or story, a dilemma or theory, a rumor, argument, confusion, war, childbirth, accidental psychedelic experience, dog euthanasia, economic indicators, toothpaste conspiracy theories, etc. It can be today’s shower-thought, yesterday’s grievance, or an idea that’s haunted you for a decade.

I hesitate to offer any prescriptive method on “how to come up with good ideas.” Sometimes they come from the belly button. My best recommendation is to write down every mild epiphany you have, ideally in prose, ideally legible enough to share with a friend, ideally 3 times per day, and if you’re crazy and jobless, 100 times per day. I’ll say this: don’t write the ideas you think you need to write about; write down what’s already passing through your mind. The best ideas come from paying attention, from patient, endless probing.

So while the idea of starting ideas is unsystematic, mystical, and mostly random, I do think there are learnable patterns in how you articulate the thing in your lap. A fisherman can go on adventures of endless variety, but there are only so many ways to skin a fish.

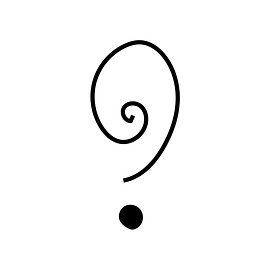

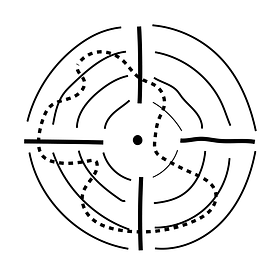

You can think of an essay as a collection of little ideas (your Material (1)) that all work together to support one big idea (your Thesis (2)), that you eventually compress into a crystallized idea (your Title (3)). Geometrically, ideas are about centrality. A bunch of planets orbit a central star that has to be named.

You can start at any scale. Sometimes you wake up from a dream with a Title that jingles. Sometimes you have a weird, specific Thesis (ie: the sitcom Seinfeld marked the decline of western civilization) but don’t have any evidence yet. Sometimes you collect a mosaic of Material that all seem connected through some invisible web, but you have to write to find out why.

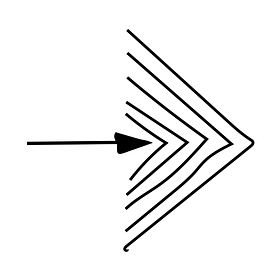

Regardless of where you start, there are two opposite modes that help you sift through an ideascape: divergence and convergence (coined by JP Guildford in 1956). To diverge is to be open and open-minded, to chase down tangents, to imagine a world of potential in even the stupidest detail, to drop all filters and see how any thing connects to everything. To converge is to be a ruthless editor. Through divergence you discover a better center of gravity, and through convergence you let go of anything outside of its pull.

It is natural to fall in love with your own ideas, but you will have to delete a lot more than you write. An essay is not a chronological record of your thinking. Drafts are meant to be shed. Writing lets you explore the edges of your terrain; but once you’ve become a parkmaster, it’s your job to pick one landmark for someone to visit. An essay is an opportunity to share a single idea at max potency. Do not try to put the whole park in prose. You’ll kill the trees. The goal isn’t to see how much you can cram (word count is not impressive); the goal is to reach the highest possible density of meaning.

The good news is, all the ideas you cut from your current essay are seeds that can sprout into future essays. Unlike books, you’ll be able to produce many essays in your life, so have faith that each idea will have its moment. Let each one breathe, and use hyperlinks if you must. Pick one idea and take it seriously.

When ideas are properly scoped and sculpted, they become linguistic viruses that enter and change the mind of the reader, so write responsibly. By unifying a multi-dimensional range of material around a kernel of truth and giving it a name, you give somebody a new lens to their reality. The essay is folk technology that turns human experience into transferrable wisdom. We could use some of that.

Upgrade to the $10/month tier to unlock all the element and pattern pages below.

Material (1)

Have you tapped into your personal and cultural memory to build an argument that supports your thesis?

Your MATERIAL is the collection of bricks that make your essay; it can include stories, memories, references, concepts, facts, statistics, quotes, etc. What you actually include is a personal decision, an idiosyncratic reflection of your life and taste. When you write from ...

Experience (1.1)

Do biographical events from your life make your thesis relatable?

EXPERIENCE is the lived events, emotions, and insights that a writer draws upon to personify their thesis. It is the most relatable kind of Material (1). You invite your reader to ...

Argument (1.2)

Have you explored two sides of an argument to come to an unexpected conclusion?

ARGUMENT is the art of gathering and interrogating your Material (1) to explore diverging points of view, to transcend tribalism, and to arrive at nuanced conclusions. To build a balanced argument, consider ...

References (1.3)

REFERENCES are the diverse array of sources, allusions, and citations that essayists weave through their work to create context, support arguments, and show authority. It is a type of Material (1) that is familiar to others in our culture. This ranges in ...

Thesis (2)

Have you organized complexity through a central idea that is concrete, contextual, and catalytic?

Your THESIS is the central idea that organizes all your Material (1). Even if drafting is an act of meandering through acres of mind, you need to be discerning in the fruits you pick and keep. If you ...

Microcosm (2.1)

Is your essay centered around a representative example that makes your thesis concrete?

A MICROCOSM is a central, tangible example that serves as the concrete embodiment of an essay's abstract Thesis (2). A good one is lucid, singular, and original. Whether an experience, object, scene, or person, it functions as a ...

Response (2.2)

Is your thesis framed as part of an existing conversation so it has societal context?

A RESPONSE is the way an essay’s Thesis (02) is positioned relative to an existing conversation or cultural work. Your essay might be a review of a movie, a reaction to another essay, or a ...

Catalyst (2.3)

Does your thesis inspire change in action or outlook?

The CATALYST is the part of your Thesis (2) that triggers a change in action or outlook, either implicitly or explicitly. Whether at the scale of the personal or societal, a Catalyst models ...

Title (3)

Have you crafted an alluring, phonetic phrase that represents your main idea?

A TITLE is the doorway into your essay; a compelling name for your Thesis (2), gives the reader an instant flash of what to expect. It serves as both an invitation into a thought-structure, and a souvenir on the way out, memorable and shareable. As media environments get more chaotic, and readers get dizzy from optionality, it becomes increasingly important to ...

Glimpse (3.1)

Does your title give an immediate impression that compels your reader to start?

GLIMPSE is the quality of a Title (3) that gives the reader a tantalizing preview of what’s inside an essay. A good glimpse is often eidetic (anchored in specific mental pictures), referential (connected to cultural nodes through subtext), and/or ...

Essence (3.2)

Have you distilled your thesis into a memorable phrase?

Your ESSENCE is the distillation of your Thesis (2) down into a phrase that shapes your Title (3). Any essay is loaded with many potential ideas, images, and phrases that could each make for an alluring and catchy title, but you want to pick one that ...

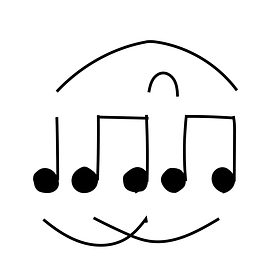

Melody (3.3)

Is your title fun to say out loud?

MELODY is the sonic quality of your Title (3). It covers the interplay of phonetic devices—like alliteration, rhyme, consonance, and syllable patterns—to create a pleasant phrase that represents your idea. You want to consider ...