How many times do you rewrite a draft from scratch before you publish it?

Once? Nill? 10 plus?

This is my 5th attempt, and it’s especially risky because my deadline is in 5 hours. Becky and I are cross-posting at the same time (8 AM ET Wednesday in Hong Kong), and my last 4 versions just don’t cut it. V1 was an abandoned book intro. V2 was 10,000 words of bore. V3 warped into an X thread that got 3 likes. V4 integrated an old “how to reverse outline” manual and turned Frankenstein. If V5 isn't shareable, Becky might hate me forever and so I really need to deliver.

This roving behavior is pretty typical for me. In architecture school I was known for making big changes to my design with 72 hours left until crit (nutso stuff). With essays, I’ll occasionally get OCD and rewrite something 17 times; but usually, it happens at least twice/thrice.

It’s not that my first drafts suck; they’re generally pretty good. It’s just that by the time I finish, I have a new clarity on its potential, and I’m blessed/cursed with the patience to do it again and again and again.

Despite being gungho for the rewrite, I’m selective about when I do it. Not every idea can or should be put through a ruthless pressure cooker. I do this for <1% of my ideas. In a given month, I’ll publish something like 250 logs that are filled with typos, maybe 5 one-page, one-take typewriter essays, and no more than one essay that’s gone through re-write limbo. I’m a big believer in fast, intuitive writing. But the ideas that really matter (maybe 2-10 per year?) are worth rewriting until they’re near perfect, and it’s worth knowing how to do that.

Rewriting is both technical and emotional. The process is analytical, but you also need a certain mindset and temperament to not wig out.

Fortunately, there’s a good metaphor we can use to welcome this process: alchemy.

It even comes with its own word: “assay.”

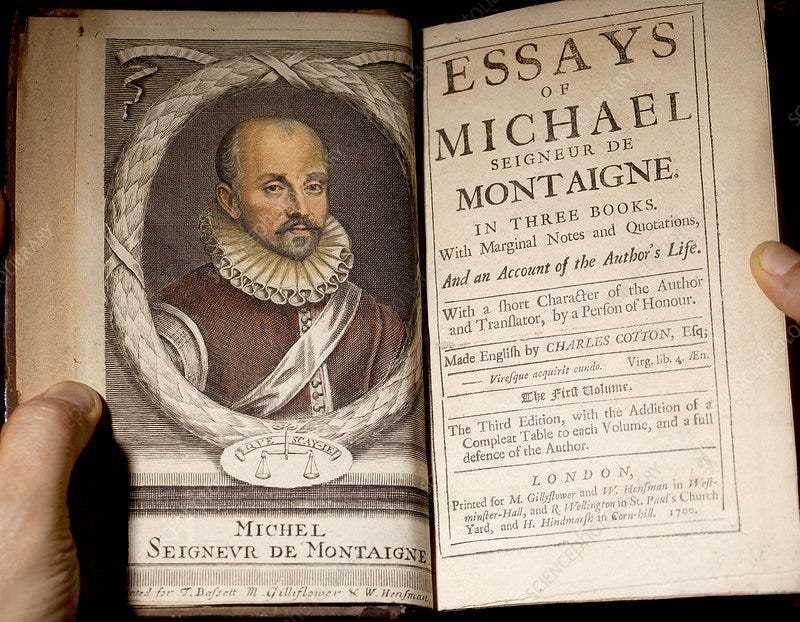

Essay vs. Assay (Montaigne might be wrong)_

We call our posts “essays” because of a French mayor named Michel de Montaigne; in the 1580s, he would retreat into a tower to write a series of vignettes called Essais. The word translates to “to try,” “to test,” but also, “to attempt,” “to undertake,” and even, “to thrust out.” All of these interpretations are process-oriented. They focus on the romantic and gushy qualities of spilling your guts into a first draft. Show up, channel the universe, spasm onto the page, and call it art. No wrong answers.

In the Montaignian sense of the word, “to essay” is to not be concerned with composing a legible linear arc; it’s the pure act of thinking and feeling into prose. To clarify, this spirit is extremely important, BUT(!), it’s only half of what’s required to be understood.

It’s weird to me that the writings of the father of the essay read like the musings of a rambler. Of course, he is historically relevant: he brought the personal dimension into short-form prose, he covered a polymathic range of topics (gallbladder stones, God, cannibals, taxes, thumbs), he was one of the first to use the printing press to make his ideas accessible to the public, and he influenced great thinkers like Shakespeare, Descartes, and Nietzsche… but Montaigne is known for tangents and digressions (and it doesn’t help that it clocks in at a 14th-grade reading level). He wanted to capture the unhinged explorations of a meandering mind. Maybe he succeeded at that, but it doesn’t lead to timeless essays.

I hope to put in the work so I can one day appreciate Montaigne, but still, I think he represents a distorted view of the writer-reader relationship. An essay is an act of communion. It’s more than riffing on the page; it’s about crafting your thoughts in a way so a reader can inherit your perspective. I sense that Montaigne is a symbol for clinging to first draft structures, either for laziness, for fear, or for the thrill of being “organic.” The order you first conceive your thoughts is rarely the order that will make the most sense to readers. I like to think the first draft is for me to discover my idea, and the second draft is to best convey that idea to a stranger.

I was shocked (and thrilled) to learn that the etymology of the word essay implies that you don’t have to edit it!

“Essay” comes from the Latin word “exagium” … and there’s another word that springs from this root: “assay.” I’d never heard of this one. I looked up both brother words in the COCA (the Corpus of Contemporary American English: a well-balanced library of a billion words that’s used to check how common a word is). Essay had 19,894 instances, and assay has 1,976 (surprisingly high, but still 10x less used).

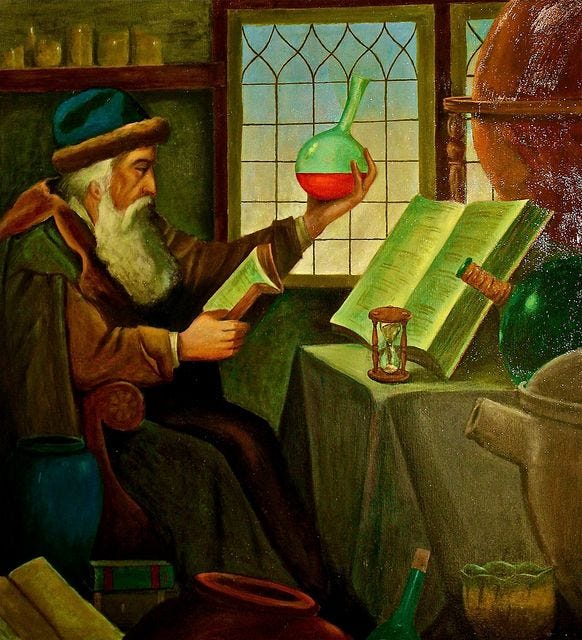

Assay was coined a hundred years before Montaigne, by an alchemist named Paracelsus (the father of pharmacology). The meaning of assay is closer to exagium, and translates to “to weigh,” “to measure,” and “to determine the content or quality of something.” In a chemical sense, these alchemists were melting materials to understand their properties.

So while “essay” is about the original act of putting your thoughts on the page, “assay” speaks to the opposite function: to analyze what was made. After all, isn’t editing an act of melting?

The alchemists get a lot of flack: they’re caricatured as hucksters who tried to turn lead into valuable metals to shill to kings. But their method–the alchemical process–is not just the precursor to the scientific method, it’s the perfect metaphor for the creative process.

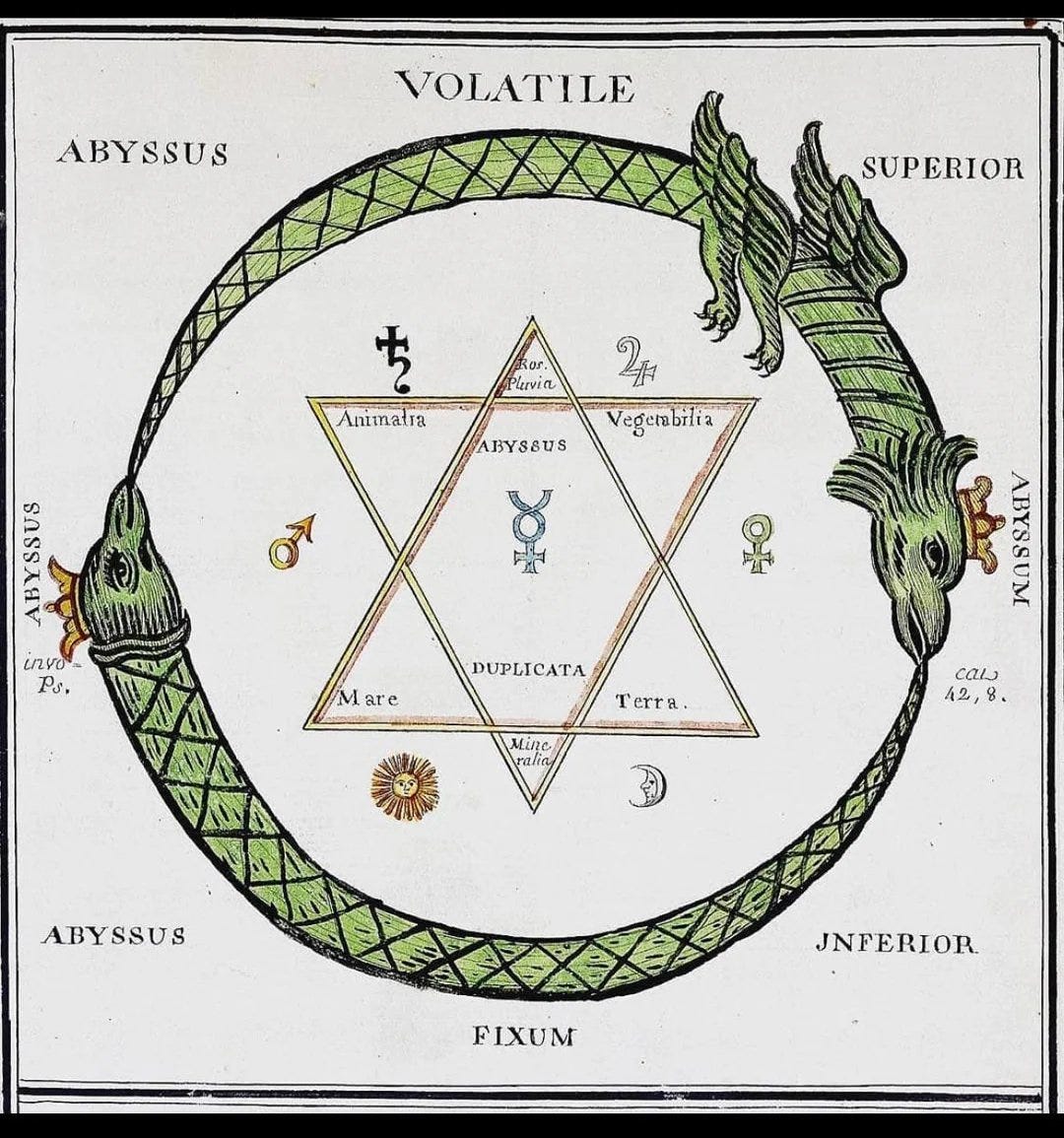

Alchemy is often simplified as “idea mixing,” fusing 2 or 3 uncommon influences; but actually, alchemy is the process of shifting between two opposite states (heating and cooling).

An alchemist starts by taking an existing metal and melting it to see what’s inside. Add heat. Dissolve the thing. Analyze the goo. Remove impurities. Refine proportions. Add new chemicals … Then they freeze it, binding everything into a new crystallized form. Once it’s solid, melt it again … The constant diverging and converging turns raw materials into refined ones.

Consider the parallel to writing: editing (or, restructuring) is the process of heating. You melt the seams that tie your prose together and analyze the ideas behind a draft. Like an alchemist, you rearrange the goo, add parts, delete parts, shape a new outline, and then rewrite it. Putting liquid ideas back into solid prose is a cooling process: you’re crystallizing thought.

So “essay” and “assay” represent the two halves of the writing process. One is about exploration, the other about examination. One is intuitive and mystical, the other is rigorous and scientific. We should honor each half, and de-latch from Montaigne’s notion that an essay is an unedited mind on the page. Like an alchemist, we should reforge our ideas over and over.

Ultimately, the path to quality comes from taking a draft, and having the courage and capacity to melt it. Academically, this process is known as “reverse outlining.” We usually think that outlining comes before the draft, but doing this after is how to start refinement. You dissolve your prose under the heat of analysis, so that once-frozen sentences are now malleable bullet points that can be reshaped into a new iteration.

The next section is a step-by-step guide on how to rewrite a draft.

How to melt your prose_

Make a backup. The idea of melting your prose sounds as irreversible as dipping physical paper in a vat of acid. Don’t melt your work without having a backup. Remember, Google Docs has a version history. You can copy text. You can copy files. You can print out your draft and store it in a safe. Don’t cling, don’t be timid, and have faith that your next iteration will be stronger. Do whatever it takes so you feel comfortable melting your precious sentences.

Find the seeds (solve et coagula). Before you melt your draft, you want to inspect it. The goal here is to identify all the indivisible units of meaning. Ideally, every paragraph is a distinct idea, but this is rarely the case in a first draft. Sometimes there are 3 ideas in one chunk, sometimes one idea is extended across 3 chunks, and sometimes it’s just a big wall of text. Sub-titles can be misleading too. The goal here is to untangle the knots: delete your headers, and re-cluster your sentences so each paragraph is a distinct unit of thought. The alchemists called this “solve et coagula,” which is Latin for “dissolve and coagulate.” It’s okay if some paragraphs are small fragments and others are huge. You can’t re-structure until you know the atomic elements you're working with. These pure and isolated components were called “seeds,” and they can be kept, cut, recombined, or transformed.

Name your parts (specificare). It’s hard to grok your structure when all your ideas are expanded as long strings of words. Unlike those aliens from Arrival, we can’t process full essays at once. In order to “think in structure,” we need to melt thousands of words into a small list of phrases that our mind can hold at the same time. To do this, give each paragraph a title. This might seem hardcore, but it’s great practice in compressing ideas and coining phrases. The alchemists called this “specificare” which is Latin for “to name distinctly.” This new list of bullets is your “reverse outline.” Like an alchemist, you are inspecting, analyzing, and identifying each element of your draft. You can go through this process in a new document, at the top of your page, with post-it notes, in Miro, or wherever makes sense for you. Remember, the goal here isn’t to fix or re-arrange; you want to see the existing arc of thinking.

Grasp the essence (quinta essentia). Scan your list of parts; is there a single bullet that seems more important, provocative, or unifying than the others? Is there some invisible theme that connects some of the bullets? After melting, the alchemists would search for the most concentrated essence of a substance, called the “quintessence,” or, “the fifth element.” It was beyond earth, air, fire, and water, and was thought to be the purest form of matter. By finding this essence (the thesis) it can transform ordinary things into higher forms (in the ideal sense: gold). Sit with your reverse outline for a bit and look for patterns. Try looking at your elements in every possible way until something pops. Write your new, refined thesis at the top of the page.

Rearrange the goo (conjunction). Now that we have a hunch for a refined thesis, we’re going to look back at our reverse outline. Which bullet points are worth keeping? What can we cut? Shuffle the parts that make sense into a new order, and feel free to add new bullets. The goal here is to craft a sequence that supports your new thesis. What is the most gripping starting point? What’s the closer? How do I bridge the two? This outline can be as lo-fi or as detailed as you want. It can be 5 simple points, or it can include multiple levels of indentations. Your new outline can go either at the top of your document or in a new one.

Write from scratch (fixation). This final act is an act of cooling: you’re turning your liquid outline back into solid prose. Point by point, I’ll convert my outline into paragraphs. I’ll often have older drafts to the side for reference, and sometimes I’ll copy chunks into my new outline. I still try to manually rewrite everything, because phrasing often comes out better on a second take. I’ll use more specific language and cut bloated words. Once the new paragraph is done, I’ll delete the reference one. Keep moving down. When I get to the end, I’ll sometimes re-read older drafts to see if there are any turns of phrases I missed.

The death and rebirth of all of your darlings_

While it helps to have a technical step-by-step, it’s worth noting the psychic toil that comes with rewriting. You don’t simply “melt a draft,” you also melt yourself. In the process of writing something, you become entangled with it. It’s not an objective idea, but it’s an expression of you, a proxy of your identity. Acknowledging that it’s flawed is an acknowledgement of your own flaws. The fact that we cling is entirely natural.

Stephen King coined the phrase, “kill your darlings,” to remind us that we have to part ways with beautiful sentences.

But when it comes to rewriting, it’s not the sentences that have to die, but the ego. It’s no wonder writers often avoid editing, it literally feels like death.

An alchemist might say that letting go and embracing death is the only road to refinement. In addition to their work with materials, they developed a religious doctrine around death-and-rebirth that paralleled their science. Carl Jung was fascinated by this: creative growth (refinement) and spiritual growth (“individuation”) were linked. The alchemists had multiple symbols for transformation: the phoenix rising from its own ashes, the green lion devouring the sun, and the ouroboros (the snake eating its own tail).

So while it’s tempting to talk about craft-specific tricks to detach from a draft (time, feedback, weed, etc.), maybe it’s worth thinking about the larger meta-skill of letting go. Maybe the thing holding us back from quality writing isn’t our technical ability, but our impatience and our fear of dissolving something we used to love. Once we can embrace a creative death, we can embrace it in other areas of our life: in old identities, in blocked careers, in toxic relationships, wherever. And once we see it everywhere, it’s not so unthinkable to rewrite an essay.

Knowing this doesn’t make it automatically easy. I still catch myself clinging to some first drafts. If you don’t cling, maybe you never liked the idea enough in the first place. But it helps to remember the alchemists. There are so many pressures that make a rewrite feel impossible, but if you dare to melt your prose and trust that something better will emerge, you can transform ordinary insights into linguistic gold.

Special thanks to Becky Isjwara for her multiple rounds of feedback on this! A common question on rewrites is, “how do you know when to stop?” The answer: deadlines. I think the best middle ground between infinite iteration and one-draft publishing is to rewrite as many times as you can within a fixed cadence. Becky is a pro at this. She publishes every week, hasn’t missed a deadline in over a year, and still gets in 3+ versions per essay. Check out her writing process in How to Substack Like a Journalist.

Let’s riff:

What’s your approach to rewriting?

Any thoughts on the alchemists?

What am I missing on Montaigne?

Considering checking out my paid tiers for more on writing. Details here.

I'm a fan of all the Latin that made it into this piece! Years ago I worked on a project building large compute clusters to process DNA assays for genomic research. This essay helped me map how the assay effort of my writing is helping me get deeper into what makes me, me. Much like assessing my own DNA.

There's a whole other bit to this though. Once one can produce essays and assays with regular frequency, one gains super powers of more accurate self triage as issues arise and perhaps, concentrated expression towards a desired state. You captured this opportunity well with the Stephen King quote and reframe. I wouldn't mind reading a piece from you focused on this idea alone.

No suprise here that Becky was apart of this. This one is so rich I know I'll read it again and again and get more from it. Well done.

I love the alchemist metaphor, it’s a topic I fell into last year through a book called “Alchemy: The Poetry of Matter” by Brian Cotnoir—been fascinated by ever since. The word alchemy alone makes anything feel more fun and exciting to me, which is exactly what I need when it comes to my editing mindset. 🧪

Your diagram showing the rearrangement named paragraphs of bullets works really well for my visual mind, and reminds me a bit of my process for UX design. Naming your paragraphs to do this is such a solid pro tip.

I have two podcast recommendations for you or anyone else interested in digging more into this topic:

1) The Ezra Klein Show: This Conversation Made Me a Sharper Editor — talks about the process of creating something from nothing, super relevant to drafting and the experience of the “rewrite” from a visual artist perspective.

2) The Ezra Klein Show: Best of: George Saunders on Kindness in a Cruel World — talks about how editing allows you to explore different perspectives or lenses of your own mindset… by the time you’re done, you may have actually changed how you feel or who you are in some small way.

🌱 Thanks for planting the seed in my mind to explore this metaphor further.