Quality is the transcendence of categories

Announcing the judges for the 2025 Essay Architecture Prize & the judging system that will shape the anthology

The deadline for the $10,000 Essay Architecture Prize is at the end of today! In addition to the grand prize, a dozen or so finalists will be published in a Metalabel anthology (which hopefully brings $1k per writer). Last call to upload or recommend your favorite essays, written in 2025, capturing the spirit of 2025.

In case you’re not aware, there is a 40-year old system that reads through all the literary essays published in North America, condenses them into a single book, a handheld thing, and then confidently claims, “these are the best American essays of the year” (it’s in the title: Best American Essays). This is a tremendous service. Do you have time to read—in addition to the torrent of your Substacks, shelves of classic books, and milieu of podcasts—several, entire publications per day? (If you do, please send me an email.1) There is comfort in knowing that, even if you fall behind your evergrowing reading queue, someone has done the hard work of collecting the essays that you wouldn’t have wanted to miss. I respect the scope, endurance, and ambition of this process. Once I heard about it, it wasn’t long before I bought the entire collection on Thriftbooks; it only costs $300 and it fits in your trunk.2

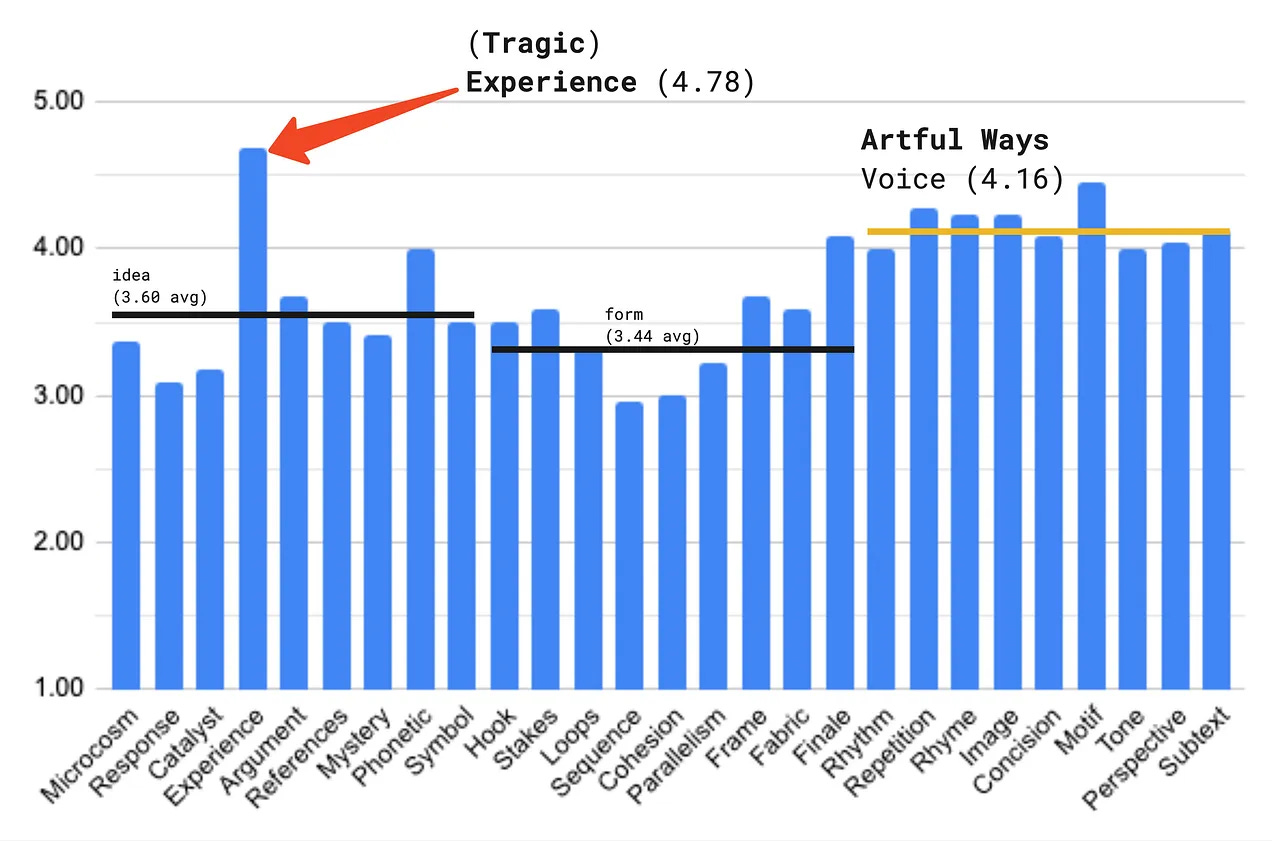

But it wasn’t until I read, scored, and reviewed the 2024 edition in full that I became suspicious of their notion of best.3 An Amazon review described the anthology as “tragic experiences communicated in artful ways.” 68% of the essays had death as its core theme, and the remaining tapped into other extreme vulnerabilities (jail, rape, gender surgery, etc.). Of course, no topic should be off limits, and a publication has the right anchor itself in a specific perspective. However, Best American Essays, at least in my mind, has a much different responsibility than The New Yorker or an indie litmag: they are the “curator of the curators.” They are the leading institute in championing the 450-year institution of the essay (a genre that has potential to become the most relevant written medium of the 21st century4—a genre not to fumble). It feels wrong to me that they’re conflating “best” with their particular agenda for the genre (an obsession with devastation).

Why does anthologizing matter? Well, what you anthologize becomes legible to the culture, and what you don’t anthologize stays unconscious. Literary movements start in the shadows and only emerge from ambitious curation schemes.5 In 2004, Paul Graham argued that the Internet—free from literary gatekeepers—would usher in “the (golden) age of the essay,6 and while I think he was incredibly right,7 he missed the fact that the whole movement might be somewhat illegible. How would you know we’re in a golden age unless you personally keep up with several thousand Substacks and review them? All year, timeless essays are casually flooding the Internet, some go viral and some go in the gutters, but everything is disaggregated, the platforms mostly care about revenue, and the word essay exists in a fuzzy limbo with its sibling genres (the article, the newsletter, the blog). If we can define WTF an essay actually is, reclaim the word, agree on what makes one high quality, build systems to discover the best ones, pay them extremely well, and assemble them into (popular) books, then we can capture where the real heart of the 21st-century essay lives.

And so the aim of the 2025 Essay Architecture Prize, in addition to paying the winner $10,000, is to assemble an anthology of high-quality writing that both captures the spirit of the year, while also showcasing what’s happening online. It’s an attempt to innovate on how you pick the winners. It’s not a single guest judge. It’s not a team of guest judges that are all slanted by the same agenda. It’s also not entirely up to my terrible8 machine. The experiment is rooted in two questions: (1) what is quality? and (2) how can we create a dynamic system of frameworks and people to agree on what makes something the best?

The quality debate:

The quality debate is a thorny one that usually devolves into “everything is relative.” I’ve talked to non-readers and even once the head of an Oxford English department, and the consensus is that any single definition of quality is too myopic. I actually agree. We have different schools of craft, different worldviews, and readers with different tastes who adore different canons, and so in a culture that is endlessly diverging, it’s fair to assume that it’s impossible to unify everything under a single, simple criterion. Even if Essay Architecture succeeds in building software that can detect all the nuances of composition, it will never be able to compute the incomputable: ethics, soul, originality. Quality is more than being well-written. It’s more than a righteous point of view, or the ability to stir up unusual feelings inside you. It’s somehow a blend of all that.

My emerging thesis is that quality is the transcendence of categories. A simple example: lots of philosophers ignore the musicality of their prose because they’re so focused on their argument; and also, a lot of literary types are so locked into the aesthetic quality of each word that they neglect the cohesion of their thesis; but then consider G.K. Chesterton, who makes sophisticated arguments in extremely phonetic ways. He transcends a boundary that often divides writers. Even though an essay can be great along any single dimension, maybe quality is multi-dimensional, fusing things that don’t gel. It’s not just power, not just range, but range x power.

So I’ve designed our judging system to have 10 people that cover three different branches. Each branch—composition, perspective, and taste—represents an opposing way to think about quality. I use the word “branch” because I see this working somewhat like the American system of government (as designed), a triad of checks and balances. There are judicial laws that evaluate the fundamentals of essay writing (Essay Architecture), a council of people that represent different corners of the Internet (effectively, the legislative branch), and then a single executive, a well-read Internet citizen with a unique ability to interpret the intangibles. An essay that excels in one branch might be weak in the others: perfect craftsmanship might be soulless, a revolutionary perspective might have choppy prose, an original might alienate the public. And so the essays that can transcend all three branches might truly earn the title of best.

What makes this maxim interesting to me is that it’s fractal: if you zoom into any branch, you realize you can only master it by transcending the inner tensions of that branch! And so, I’ll write a quick paragraph on each one, so you understand how it works and who the judges are.

Composition:

The Essay Architecture app will score all uploads 1-5 on 27 patterns, make the longlist of the top X%, and then I’ll manually rescore to confirm accuracy and make the shortlist.

My framework is an attempt to define the essay at the genre level, but the common question is, “does every essay really need all 27 patterns?” The essay has many sub-genres that only care about a subset of patterns—the personal essay, the fragmented essay, the braided essay, the lyrical essay—but this constrains it to a particular type of reader. The essayist has the ability to touch all sides of the psyche, to fuse the soul of a memoirist, the rigor of a philosopher, the pen of a poet, the persuasion of a marketer, the research of a journalist, and the imagination of a novelist. The “unitive essay” can transcend all those archetypes into a single thing, and we should celebrate the ones that do. Here’s a library of examples, where the score represents ‘compositional well-roundedness.’

Perspective:

A team of 8 judges, each with their own speciality, will score each essay on the shortlist over three subjective criteria.

A reader is often drawn to a writer because of a worldview, a vibe, a perspective. They might care less about the craftsmanship of the writing, and more about the specific angle towards the world. Unlike the patterns in composition, this is mostly subjective. It’s hard to say if one perspective is better than another, but we could measure “inter-subjectivity,” the resonance of an essay across different judges. My goal was to assemble a team of writers and editors who each represent a distinct sphere of online writing culture. Our team has doctorates and comedians, memoirists and journalists, people with different temporal lenses, to the past, present, and future.

Judges will score each essay on the shortlist across three questions, each colored by their perspective: (a) do you like it? (b) do you think it captures the spirit of 2025? And for (c) each judge gets to shape their own question. Here are the judges (A-Z) along with their question:

Charlie Bleecker: “Does it elicit powerful emotions?” She’s published almost 300 weeks in a row in Substack, including personal essays, newsletters, and 62 episodes of Memoir Snob, where she explores the nuances of writing from Experience (the defining pattern of the essay). She fearlessly puts her life on the page, and is becoming an expert at articulating the techniques of relatability.

Alex Dobrenko`: “Is it funny, honest, and true?” He writes Both Are True, a top comedy Substack that is a sweet mix of zaniness and vulnerability. Alex is the sensei of “platform tilt,” a technique in making and breaking frames, where you are constantly falling through the floor and laughing as you do it. In contrast to the schoolish definition of “essay as bullshit homework,” Alex shows that an essay can be a labyrinth of jokes that coax you into the heart of something real.

CansaFis Foote: I tried to finagle some criteria out of him, and the best9 we could agree on was “Is this essay a fusion of pensive apeman and unbarnacled starfishman using deep gazpacho technology to capture the human lotto scratch off vibes of harmonized tubular audition tape?” Said otherwise: “Does the writer bring a unique essence to the topic at hand?” Mr. Foote is a subversive essayist, a corporate jester, and eventual host of bingo night at the Sphere. I became an instant fan when I read his essay written from the perspective of a squirrel.

Elle Griffin: “Does the essay bring a solutions-oriented mindset to an important problem?” Elle is the founder of the The Elysian Collective, a publication dedicated to futurism and utopian thought. Historically, the essay has been a vessel for civic imagination, and Elle is committed to use her writing to help design the future we want. In that spirit, she’s pioneering new models of crowdfunding, community, and print publishing.

Lellida Marinelli: “Does it have an essayistic mode of thinking?” An Italian scholar with a PhD in essayists writing about essays, she is extremely knowledgeable in the history of the medium, specifically on how writers have reflected on the genre and process. Check out her academic papers. I’m excited for her to see if century-old traits—complexity, lyricism, heresy, etc.—have organically re-emerged in online writing.

Dylan O'Sullivan : “Does it grapple with the timeless human condition?” He’s the Senior Editor of Infinite Books and a digital custodian of the canon (bringing C.S. Lewis, Dostoyevsky, and ilk into our feeds). He’s ingested an incredible amount of information and has put together encyclopedic indexes on rhetorical forms and the writing life. Excited for him to bring a historical lens to essays written in 2025.

Jasmine Sun: “Does the essay offer a unique way to understand a world in flux?” Jasmine is an “anthropologist of disruption,” was a product manager at Substack, and co-founded a techno-optimist publication called Reboot. She’s interviewing people at the edge of culture and tech, and has a sharp sense of the forces shaping the moment.

Isabel Unraveled: “Is the essay grounded in hope?” Isabel is a creative guide and writer who explores the intersection of intuition and expression. She helps writers—including me—break through different layers of psychological resistance. Beneath her notes and essays is a trust in the process, a sense that through hope and action, writing is an act of personal transformation.

Taste:

A single judge, the wildcard, will rank essays however they like, ideally to capture the intangible qualities of an essay.

While composition is about timeless patterns, and perspective is about cultural vectors, taste is about the discernment of a single, trusted reader. What makes good taste? I need to think/write on this more, but for now I’d argue it has two halves. First, it requires someone to absorb a substantial amount of cultural works, which gives them both a map of what exists, along with the embodied experience of feeling and reacting to different types of things. Second, it requires an ability to notice and articulate why a small portion of what they’ve seen is particularly special, even if the culture finds it weird or difficult. Taste, then, is high exposure x high selectivity. When a well-read reader absorbs something new, it gets located in their map— consciously or intuitively—and it’s processed as familiar or strange (Harold Bloom says everything in the western canon is united by a “strangeness,” an original vision that transcended the expectations of its time). Someone with good taste is in a position to articulate intangible qualities—originality, ethics, aliveness—because they are evaluating through deep context and the depths of their experience.

I’m thrilled to announce that our guest judge for this branch is Henrik Karlsson, the writer behind Escaping Flatland. Not only is he an astounding model of a modern essayist, but I think he’s the perfect counterweight to the Essay Architecture system. While he is similarly inspired by Christopher Alexander—and has even written about pattern languages in essays—he also describes essays as “forcefields of energy” on the How I Write podcast. I think he’s onto something in his latest essay on non-linguistic thinking, and hope this judging experience lets him advance his ideas on how to somatically evaluate ideas without words. Henrik recently shared his rigorous reading process along with a list of 71 books. My sense is that he is a synthesis of two very different archetypes: the topologist and the animist; his list spans poetry, systems thinking, the diaries of mathematicians, and the biographies of filmmakers. He’s curated a rare mix of inspirations, and I’m excited to see how he responds to the essays in the shortlist. I’m not asking Henrik to score anything 1-5, but to read them, to reflect on them, and then rank them according to whatever criteria feels salient.

Last push, let’s make an essay book:

What kind of essays will emerge from a system like this? The goal isn’t to define quality with an absolute or singular definition, but to create a living process where the winning essays are the ones that transcend fractal systems of interlocked tension. Each of these branches represent 1/3rd of the decision.10

The deadline to submit is today, Sunday, November 23rd, at the end of your day. The reading window will be December 1st–21st, and we’ll announce the winners and anthology in Q1 of 2026. I can’t wait to have a single artifact that (1) represents 2025 through a mosaic of essays, and (2) captures the energy of the online essay movement. Most of the people in my non-Internet life have only a fuzzy idea of the world I exist in, and so I’m excited at the prospect of handing them a book that has a decent possibility of blowing their mind (I believe great essays harbor the potency of literature in a single sitting). Hopefully, the anthology gains enough momentum to help spearhead a 2026 essay prize, too.

Some ways you can help:

Submit essays you’ve already published this year that capture the spirit of 2025. You upload through the app, get feedback (which at this point, you can likely ignore since it’s the last day), and then you’ll see a ‘Submit’ tab on the right. You can use the code ESSAY-PRIZE-2025 to claim a free upload credit today.

Share this, either by restacking, or by sending it to your friends and favorite writers.

Recommend your favorite essays from the year in the comments (or feel free to message them to me directly).

Thanks for following this experiment; excited to share the results!

Footnotes:

This sentence started as a joke that I thought I would cut, but now I’m actually curious. If the goal in 2026 is to curate the sprawling mass of Internet essays, there is an unreasonable amount of reading to do, even if AI helps with curation in some sense. Still need to actually think through this, but if you have a general interest to read/analyze a high-volume of essays next year, or if you’re already reading a ton of online essays, email me at michael@michaeldean.site and we can brainstorm how to work together.

I should probably explain why I had 40 years of essay anthologies in my trunk, but I am past my deadline so I will keep it a mystery for now.

There is a history of debating the process; here’s an excerpt from DFW’s 2007 intro when he was the guest editor:

“Just about every … word on The Best American Essays 2007’s front cover turns out to be vague, debatable, slippery, disingenuous, or else ‘true’ only in certain contexts that are themselves slippery and hard to sort out or make sense of—and that in general the whole project of an anthology like this requires a degree of credulity and submission on the part of the reader that might appear, at first, to be almost unAmerican.”

Manifesto in progress: here is my v1 mission page, where I try to articulate why I’m focused on essays and not other genres of writing. The title might be a bit dramatic, “essays are the foundation of a free-thinking culture,” but a key thing I want to get at is the potential effects of mainstreaming the essay. The BAE movement seemed very interested in reviving the status of the essay within literature (E.B. White called the genre a “second-class citizen”), but given the essay is a ‘folk medium’ (the barrier to entry is way lower compared to novels/poetry/etc.) it could have unique effects outside the literati.

Eventually, I’d like to find a whole range of examples where literary movements start from curation, but the one that comes to mind is the Beat Generation. Kerouac wrote all of his novels in obscurity, and it wasn’t until Ginsberg’s Howl popped, years later, that they asked him, “where are the other beat writers?” Ginsberg’s success put him in a position to map out and curate the movement. There was a six-year lag between the writing and publishing of On the Road.

I think it’s become trite to declare any sort of new activity as a “golden age,” and am now shy to use the word myself. The better question, what would need to happen for us to be in a golden age? Which metrics matter? Total volume of essays? Number of essayists that make money? Breadth of topics? Range of experimentation? Quality of the essay anthologies? A shift in locus from one institution to another? Maybe you can tie different words to different metrics (a surge, a revival, etc.), but a golden age, possibly, means all of the metrics are simultaneously peaking to the point of being a historical anomaly.

How is it possible that a bunch of self-taught writers might put together better essays than people with English degrees, MFAs, and status badges from notable magazines?

I have a guess: the independent writers who operate in the free market of readers have more incentive to improve. They publish, get instant feedback, and publish again, either a week or month later. They have total autonomy to evolve their topics, their forms, their voice. They need to put in the work to make something great (it’s not enough to get a commission, and to make it good enough to live in the magazines). What the independent writer has is more feedback, more speed, more freedom, more stakes. Compare this to the writers who swarm the literary institutions: they often get no feedback, publish a few times per year, have to conform to the house style, and the publication carries all the stakes. So even if literary writers have something like a 5-year head start, self-taught online writers have a higher slope of ability.

At risk of sounding simplistic: institutional writers write for editors, but independent writers write for readers.

I don’t mean terrible in the sense that it’s bad, but in the root word terror, as in, I think there’s a natural anxiety and intimidation in getting your essays judged. Will have to write more on this, on the virtue and challenges of being an anti-sycophant, and on the responsibility of creating a system that gives precise numerals that might play a role in shaping one’s compositional identity, especially if the AI is not perfectly accurate.

The runner-up criterion for CansaFis was evaluating essays entirely through the lens of the 1989 movie, Point Break, starring starring Gary Busey and Anthony Kiedis.

Each branch will be normalized and dynamically weighted. To be more specific: 1) Since the range of each branch might vary, I will use percentiles between the min and max values. 2) Instead of averaging each category (where each one is 33%), I plan to weight each entrant so their best branch is 50% of their score, their middle branch is 30%, and their last branch is 20%. Through this system, someone who wins a given branch but performs lower in the others (40/20/100), will rank better than someone who gets the median score in every branch and is not exceptional to any of them (50/50/50).

This is so exciting

I don't think I'm quite advanced in my writing to enter this just yet, but I'd love to in future. What a line-up of judges too! Can't wait to see the results.