Form

Have you designed a bold, linear path so a reader without context is both oriented and intrigued?

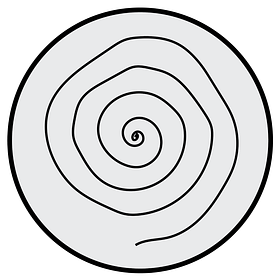

In the science-fiction movie Arrival, there is a species of octopus-like aliens who read non-linearly; they communicate through intricate rings of ink, and are able to process the beginning and resolution simultaneously. Unfortunately, our readers are not atemporal aliens. Humans read linearly. We are trapped in time. Since all essays have a start and end, we need to think about Form, the linear path we arrange through our Material (1).

Conceiving, editing, and polishing form is one of the hardest aspects of essay writing, and so, naturally, writers have invented all sorts of ways to devalue it. The most common way is to ignore it: “as long as your voice is distinct, form doesn’t matter,” or, “however it comes out is the way it’s meant to be,” or simply, “first thought, best thought.” Some historians even imply that since the first essayist—Montaigne—went on epic digressions, that we have permission to do the same. All this ignores the curse of knowledge. The reader does not have all, if any of, the context that you have, and so if you ignore form, it’s like dropping your reader in the middle of a corn maze.

The other way to deal with form is to tame and trivialize it. Consider the Five Paragraph Essay, the Heroes Journey, or any prescriptive outline that suggests a tried-and-tested trick to avoid the terrors of structures. This makes form easy, mechanical, and predictable, but it often feels like you’re trying to cram a unique idea into a generic template. This happens in architecture too. In 1900, Frank Lloyd Wright wrote essays lamenting over cookie-cutter floor plans being stamped a million times across America.

Wright advocated for an approach called “organic architecture,” which is not about curved buildings, but about letting Form emerge from the specificities of each design problem. For building design, you need to understand the unique properties of a project—the site, the climate, the views, the program, and the clients—so that a 1-of-1 solution emerges. Through understanding the constraints in such high detail, the answer comes through organically.

In writing, this means that you can’t intuit the Form of your idea until after you’ve explored your Material through drafting. Each idea is its own beast, and it’s your task to discover the form it warrants. Your first draft is for yourself, your second draft is for a stranger. First you find it, then you convey it.

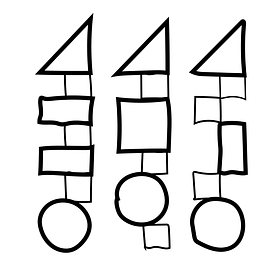

While a universal “template” would make every essay look the same, a series of granular patterns would lead to an endless amount of combinations. The smallest patterns of structure help us scope and shape Paragraphs (04), our main unit of essay composition; the biggest patterns of structure help us build Tension (06) so the reader instantly and continuously cares about the topic; and the middle patterns of Structure (05) help us arrange, select, and detail sections so the reader is always oriented, never confused.

There are two opposite modes required to discover your form. To essay means “to test” ideas by putting them on the page, but to assay means “to evaluate” those ideas. Assay is an under looked word in regards to writing, but it shares the same etymology with essay, and has alchemical undertones around melting and understanding the properties of something. You have to look carefully at what you’ve written and ask what is this? in a variety of ways. Are these two paragraphs serving the same point? (If so, combine them.) Does this section even relate to my thesis? (If not, delete it.) Does this one sentence capture the whole dilemma of the essay? (That could be a solid hook.) This is very much an act of logos, meaning, it requires the rational mind to label, categorize, judge, omit, and shift, making decisions around linearity, hierarchy, proportion, modularity, and parallelism.

This is also avoided because once you really start interrogating your form, you realize you have to start over. By thinking through Form, you often rearticulate your Thesis (02) in much higher resolution; this is exciting, until you realize you can’t manifest it through line editing, you have to redraft. Creative destruction is an unavoidable part of creation. Great essays can take 3, 7, or 15+ revisions to get right. Of course, it would be hard to run all of your writing through this intense alchemical process, but it’s worth it for the ideas that matter most to you. The more you do it, the less intimidating it becomes, and I find that only when I really wrestle with and rewrite my ideas do I advance my thinking on them.

Editing is really an act of pain transfer: grappling with the challenges of structure leads to a better time for the reader. Good structure is invisible. The reader is able to navigate through a vast terrain, but never struggles too much because the path was designed so thoughtfully. Your essay is something like a guided-meditation of linguistic epiphanies. It lives beyond you, and anyone who moves through your bold, linear path gets to have an asynchronous conversation with you.

Upgrade to the $10/month tier to unlock all the element and pattern pages below.

Paragraphs (4)

Do most paragraphs open with tension, move with flow, and close with reward?

E.B. White said that the PARAGRAPH is the atomic unit of composition. An important rule of thumb is to treat each paragraph as a discrete idea, its own room in a house of ideas. This means that paragraphs actually ...

Frame (4.1)

Does each paragraph start in a way that orients and intrigues?

A FRAME is the gateway into a Paragraph (4). Unlike the mechanical topic sentences of academic writing, a powerful frame has three jobs: (1) it orients through compressing the essence of

Flow (4.2)

Are sentences shaped and linked to be easily understood?

FLOW is the way you design and connect sentences. When you’re crafting any given sentence, you have to make tons of tiny unconscious decisions about order, detail, logic, parallelism, and punctuation. Not only that, you have to consider ...

Finale (4.3)

Do paragraphs end on a reward?

The FINALE is the closing sentence of each Paragraph (4). Of course, there is no standardized way to do this, but a powerful, literary reward is a good way to finish one idea before moving on to the next. You could use a ...

Structure (5)

Have you selected, arranged, and detailed your material to minimize confusion?

Your Structure (5) is like the floor plan of your essay, determining where each Paragraph (4) ultimately lives. It is logocentric: you can use reason to make decisions around linearity, cohesion, and hierarchy. These decisions, however, aren’t straightforward. Structure is something like ...

Sequence (5.1)

Is your material arranged so that meaning compounds gradually?

SEQUENCE is the deliberate ordering of the Material (1) in your essay. There is no universal template that works for all essays. It doesn’t have to be chronological. Rather, a good sequence organically emerges from ...

Cohesion (5.2)

Does each paragraph support the thesis to keep it focused?

COHESION is the sustained advancement of a single, specific Thesis (2) through every Paragraph (4) of an essay. Of course, related Material (1) and themes can be interwoven, as long as they ...

Modularity (5.3)

Are paragraphs and sections sculpted in a way so that your logic is intuitive to readers?

MODULARITY is the organization of ideas based on semantic relationships to aid in reader comprehension. This happens at multiple scales: clustering is about grouping Material so there’s one unique idea per paragraph; parallelism is about ...

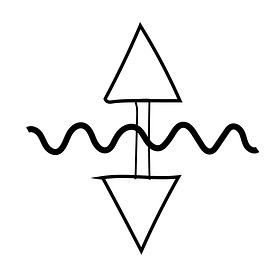

Tension (6)

Are you creating stakes and anticipation so the reader cares what happens next?

Questions demand answers. Tension is the art of creating uncertainty and stakes to compel a reader forward. We have an innate need for resolution; humans can’t bear the unknown. In nonfiction essays, you can imbue tension into ...

Conflict (6.1)

Have you set up a core tension that gets the reader to care?

CONFLICT is an archetypal sequence of Material (1) that builds and releases Tension (6). Both characters and ideas can follow this pattern: 1) a foundation establishes goals, stakes, traits, constraints, and relevance, 2) an ...

Threads (6.2)

Do you shift between multiple conflicts so the reader is immersed in evolving tensions?

THREADS are the distinct streams of drama in your essay. They are skewers of Tension (6) that open, close, interweave, and combine. A thread is more than a recurring theme, it ...

Hook (6.3)

Does your opening create uncertainty and foreshadow the core themes?

The HOOK is the opening of your essay. It can refer to the first sentence, paragraph, or section that intrigues the reader and orients them to the themes ahead. Its core job is to establish ...