As a young architect reading The Fountainhead in architecture school, I picked up a dangerous virtue: you can just scrap everything and start over. (Spoilers ahead.)

Howard Roark1—the protagonist, an architect—is the patron saint of creative destruction:2 after a building committee compromised his plans, he felt a moral obligation to demolish his own building. He used dynamite in the middle of the night. They arrested him. In court he defended himself with a 150-page speech on creative integrity. I saw this as permission to set an unreasonable quality standard for myself. Since then, I’ve been open, perhaps too open, to scrapping a perfectly-fine design to chase its always-elusive potential (this essay is v7.2, and a trusted editor begged me to ship v4.3).

In architecture school, I became known for a design-until-the-last-minute philosophy. The open problems of my design haunted me more than the fear of not finishing in time. I’d make major overhauls, days before crit, while most other students were in production mode for weeks. Through all-nighters and clever production techniques, I somehow pulled it off. The compulsion to take projects further and further let me grasp the process and patterns of architecture in a way I would’ve never known if I stopped when I was supposed to. It gave me a confidence that would eventually screw me. In my final year, the assignment was far bigger in scope, and I showed up to crit with no final drawings, sleep-deprived, rambling through 45 linear feet of chaotic design sketches. I got in trouble, but at least I passed; a friend with the same philosophy failed the semester and couldn’t graduate (Roark failed out of architecture school too).

All this to say, I know both the pain and potential of creative destruction, and in April I had to decide whether I should ship Essay Architecture or burn it down.

This decision was hard because I’d been working for 10 months towards specific forms: a 50k-word wiki on writing theory, a 2,700-point control set of classic essays, custom-built evaluation software, sleek visual interfaces, and some active users—but I didn’t have the one thing that mattered most: high-quality feedback. It was, despite my best efforts, slop-prone. But as I reflected on the dilemma, I had an insight: through building and failing, I gained a hunch on what it might take to make an AI-powered editor that doesn’t suck … all I had to do was completely start over.

It was a gamble. Either I invent something that’s massively useful for writers, or it doesn’t work and I have nothing to show for a year of effort.

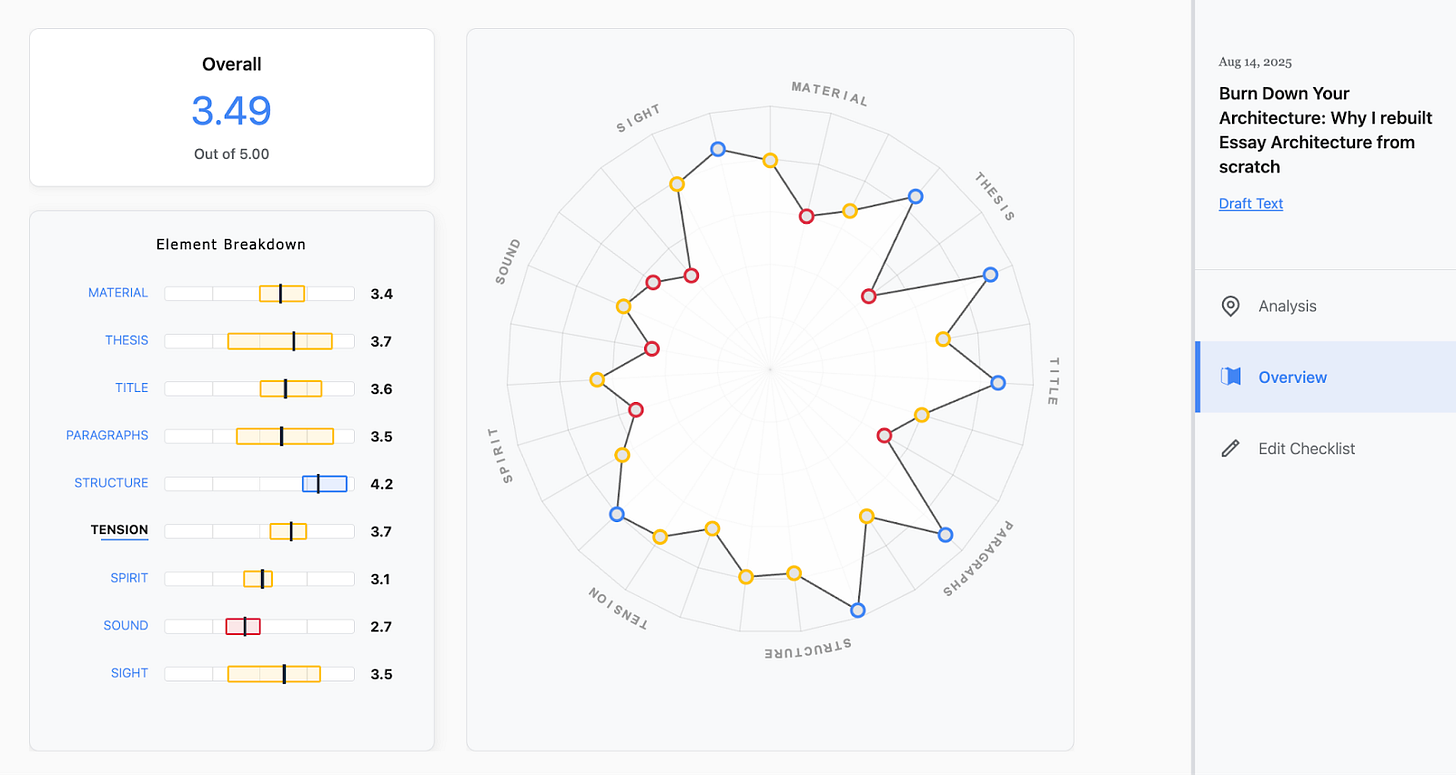

The beauty of a blank slate is that you have way more context and the freedom to ask a more specific question. What if essay scores don’t matter? What if the only goal was to shape an AI to give specific, contextual, useful feedback? What would it take to build a world-class editor, always available, for like $9/draft? (One that refuses to write for you, BTW). So I rebuilt it, and while the feedback was noticeably better, something more interesting happened. Only when I stopped obsessing over score precision did I accidentally build something that is 47x more precise than Claude Sonnet 4, the best public chatbot for feedback.

This post is an update on year one of Essay Architecture (how it went, what you’ll soon have, and what’s next), but more so it’s a reflection on the nuances of creative destruction. Whether you are making software, a company, a building, a book, a song, an essay, or whatever, it’s worth knowing what you gain from burning down your architecture.

Design through destruction

At the core of creative destruction is a simple idea: be thesis-driven, not form-driven. This means you’re not tied to any one particular form; you burn through them to find one that embodies your thesis. The challenge is, you can’t really see your thesis in high-resolution until you cast it into matter. You have to start somewhere. But in order to start anywhere, you have to make assumptions, and many of those will be wrong, and you won’t know which ones are wrong for weeks or months, if ever. Some assumptions are small and fixable. Some assumptions are big and irreversible and set your project’s fate.

An “original sin” is a foundational, day-one mistake that all further decisions are built upon. I had two.

The original sin of my textbook was the ambition to make each chapter as gnarly as possible. I assumed the book should be physical, held in hand, the culmination of everything I ever thought about writing. I started off by shipping 5,000-word prose essays, each with a dozen custom illustrations. They took 50 hours each. Whatever it takes to make Elements of Style for the 21st century, that’s what I’d do. But if I need to do that for every pattern, element, and dimension, then it demands like 38 hours of full-time work per week, on just the book.

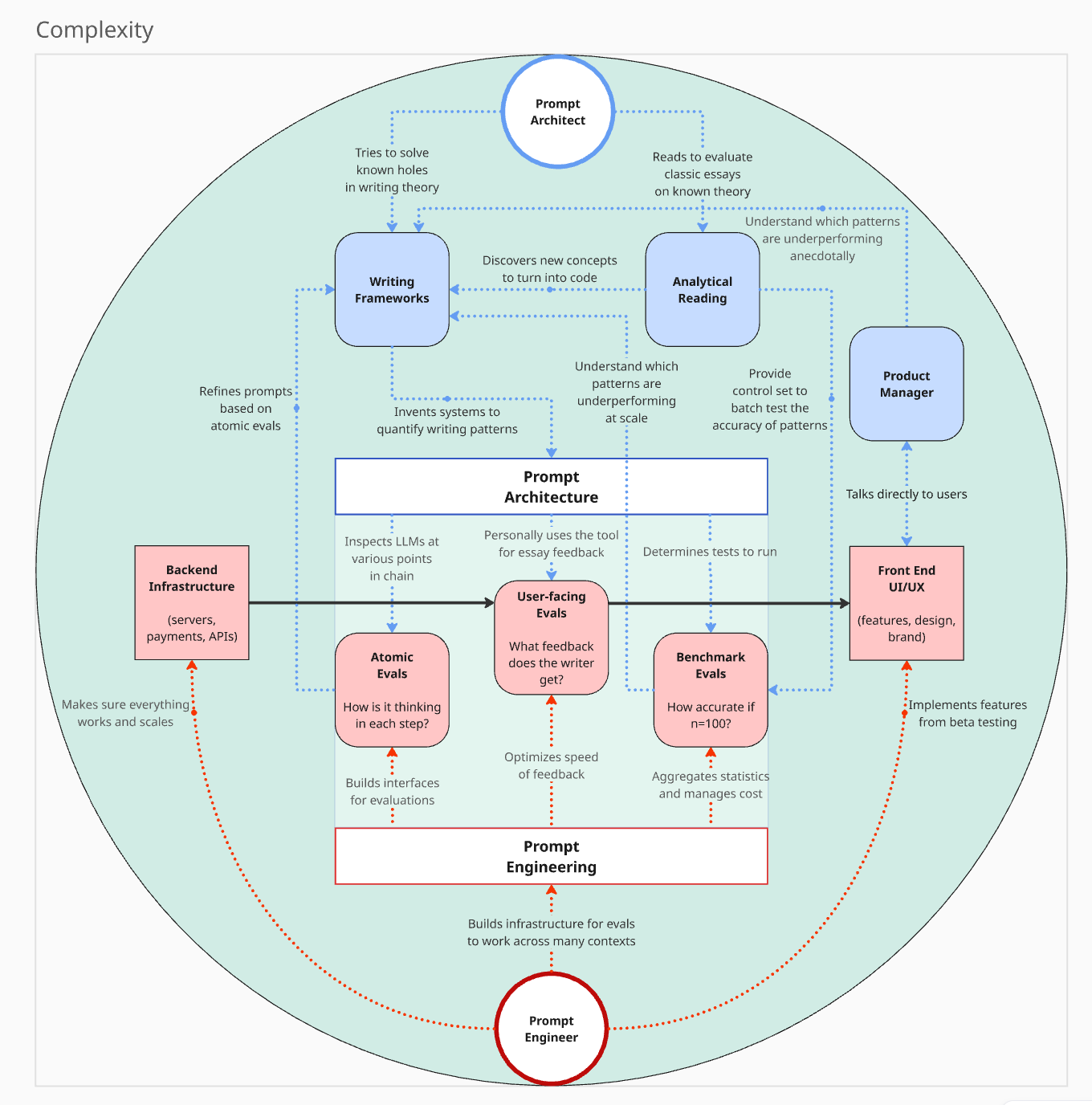

Once I really got into building software and grasping the complexity, I realized I had something like 8 full-time jobs of technical work cut out for me.3

The dilemma became clear. I couldn’t focus on the book and the tool: if I approached both forms, I’d have neither. And so I had to burn the book, and melt it down into more and more compressed forms, until it was no longer a book, but a wiki that lived directly in the software.

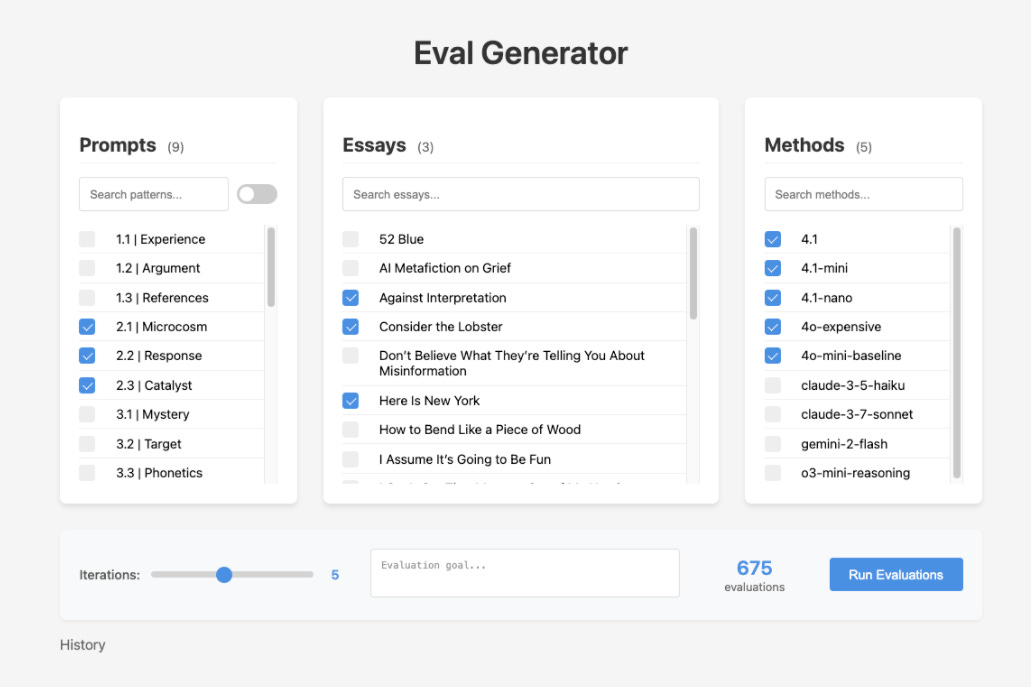

The original sin with the software was that I accidentally built “hot or not but for essays.”4 I was obsessed with scoring, not just because I am a numbers guy,5 but because quantifying quality was the only way to ensure that an LLM was not bullshitting you. I scored a hundred essays 1-5 on 27 criteria, and then built a whole suite of admin tools so that I could run hundreds of evaluations with a single click—to test variations of patterns, essays, and models—so I could recursively improve my prompts for higher accuracy, precision, and reliability.6

Through rigorous testing I was able to get patterns to match my control set by 80-90%, but I didn’t realize I was getting captured by my own metrics. Yes, it could think and score like me, but I overlooked how these numbers converted back to written feedback. It was sometimes useful, always vague, and often, completely useless:

“To improve, the author could enhance the richness of the narrative by incorporating a wider range of cultural touchstones and specific examples, which would not only ground the philosophical insights but also create a more relatable framework for readers.”

Yikes. So I shifted my attention to making the feedback better, and it did get slightly better, but I hit what seemed like an unpassable limit…

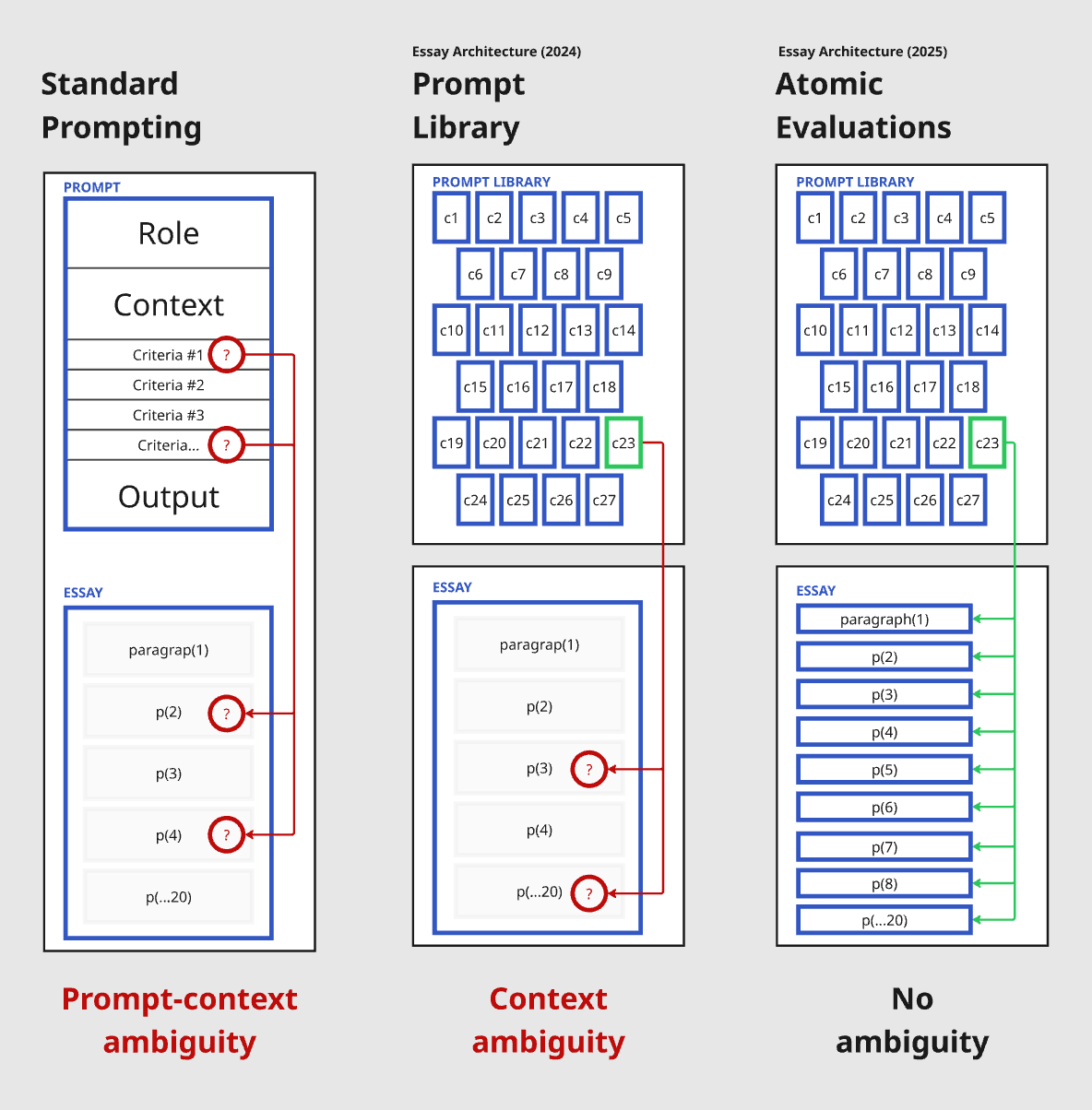

Since my engine was built on determining the overall score for a pattern, it didn’t have a paragraph-by-paragraph coherence of your essay. This is what a good human editor intuitively has: they understand your essay at different scales—the word, the sentence, the paragraph, the section, the whole—and can navigate between them. When I inspected how my evaluator was thinking across iterations, I noticed it would pick a random paragraph each time, and use it as the basis of big-picture feedback.

This was unfixable.

Once you grasp the nature and magnitude of an original sin, the only way forward is destruction. There is no degree of polish or patchwork that can fix a flawed foundation. At first, it’s demoralizing. But it isn’t wasteful to shed. Your abandoned forms are vehicles to refine your assumptions and discover your constraints. If you believe in the spirit of iteration, then design is 50% destruction.

So I started over with a new assumption: AI feedback sucks because of “context ambiguity.”7 It gives random results because it’s never sure what to focus on. What if I isolate the scope? What if I run every criteria against every paragraph, so that the goal is extremely clear?

So I built out a new method, and as far as I know it doesn’t have a name, so I’m calling it “atomic evaluations.” It runs 1,000-10,000 evaluations for every upload, and bridges the macro and micro scales. The downside is that it’s slower (~15 minutes) and more expensive (sometimes $3/draft in API credits). The upside is that it’s like “DeepResearch but for essay composition.” It takes time, but the feedback feels contextual, specific, and more like something I’d get from a human editor:

“Can you explore the origins and cultural weight of the "kill your darlings" writing adage?” (Paragraph 4) [then, if you click to expand, you get more details] … “You mention this common phrase, which sets a useful tone, but it feels like a missed chance to connect it to rich literary or historical roots. Could you explore who first coined this adage, how it shaped literary writing traditions, or how its meaning evolved in writing pedagogy? What stories or controversies surround its use? Elaborating in this way will ground the metaphor in tangible history, making it resonate more deeply with readers. And how might knowing the phrase's origin deepen your thesis about iteration and destruction in writing? This is where layering in archival or scholarly insight can really shift your essay from naming conventions toward meaningful scholarship.”

It also turns out that granular analysis doesn’t just lead to better feedback, it leads to extremely stable scores. I asked three instances of Claude Sonnet 4 to score the same essay 1-5, and it returned 3.25, 2.75, and 3.45. I ran the same experiment through Essay Architecture and it got 2.93, 2.92, 2.93 (in this example, the range of variability is 47x tighter). Over multiple examples, my overall precision score still holds at 99% (compared to Claude’s 83%). The accuracy still needs work, but high precision means we can get LLMs to think in predictable and reproducible ways. It means we’re not technically limited; we’re only limited by our ability to turn writing theory into code.

When you abandon your old forms and tighten your thesis, something magical happens. Not only are the new forms more mature, but in some unexplainable way, the old forms remerge without you trying. I hesitate to use a phoenix metaphor, but when you let something die, something better grows from its ashes. Only after abandoning score precision did I—in pursuit of a better goal—invent a system that accidentally led to hyper-precision.

To my surprise, the same thing happened with my textbook (which I declared dead in January).

The book phase-shifted into the wiki, but the wiki had its own troubles: it was an intimidating maze of text, too distant from the incoming feedback. And, so again, the form started melting: from full pages, to hidden paragraphs you reveal, and finally down to a single question per pattern. This compression was driven by the medium (prose works very differently in a web-app than in a book8). I realized I had to build my curriculum like those Russian Matryoshka dolls; each pattern now exists at multiple resolutions: small (a 10-word question so you instantly get it), medium (an 80-word blurb of your choice), and large (a 500-word modular page). Since Essay Architecture is both wide and deep, I need to present patterns at their smallest resolution and let writers opt in for complexity when they’re ready for it.

Only after I built out a digital fractal curriculum did I realize, oh wait, this could totally be assembled into a book. In a single day, I aggregated everything into a gDoc and used my essay, A Pattern Language, as the introduction. It landed at 20k words and I’m almost done editing. It’s smaller, and quite different from the original vision of illustrated prose essays, but it’s very distilled, and perhaps the best way for someone to wrap their head around the entire framework in 1-2 hours.

Essay Architecture goes live!

On September 15th, you’ll be able to read the book and use the tool. I need to thank everyone who has been following this project for their patience! My paid subscribers (to date) will get the ebook for free, along with some credits to try the tool. If you filled out my survey to join the beta, expect to receive an email next week for early access.

As I imagine the months and years ahead for this project, I wonder how I can embody creative destruction to its fullest. Even though I logically know and value this virtue, it is very easy for me to fantasize about form. For example, on September 15th, I also plan to launch an essay competition (announcement coming soon!); the natural instinct is to envision all its features, the user experience, the operations required, etc. Instead, I’ll be starting from a question, “what can I learn from running an essay competition?” There are many unknowns, and thus many assumptions—what might be my original sin?

To clarify, you definitely shouldn’t burn down everything you start. There is wisdom in knowing what’s worth letting be, and what’s worth obsessing over. In some cases, expression only warrants a single take. There’s also a case for engineering to be non-iterative: eventually you want stable, scalable infrastructure. But the act of creating in unknown realms should be conceived as an experiment: you build not to finish, but to learn and rebuild.

I sense that most creators shy away from experiments because creative destruction is … destructive. We cling. If you write, you likely know the phrase, “kill your darlings.” It reminds you to delete that one sentence you fell in love with because it no longer serves the essay. This phrase traces back to a 1914 lecture from Arthur Quiller-Couch, where he said “murder your darlings.” This deliberately-violent phrase incepted the idea that, to move forward, you have to delete sentences; we don’t yet have a phrase to delete all of your sentences. We also don’t have the incentives. Algorithms create a high-speed culture that rewards quantity over quality, and also, the pursuit of quality is not just inefficient, but often lonely and painful; it challenges all of your internal mental limits. I imagine that when you’re writing, there’s a voice in your head hoping, “maybe this is the one, maybe I can ship this draft.” I know this because I have this voice too. God, don’t make me write v8.1.9 But this comes from impatience, and from confusion over the whole point of a draft, which is never to finish, but to put you in the right place to ask the right question: “now that I know what I know, what could I make if I start over?”

When was the last time you started over on a project, and how did it go? How do you approach something when you know it’s sacrificial? What are you holding onto that you should let go? When is it worth not burning down your architecture? Questions about Essay Architecture?

Footnotes:

I have to eventually write an essay about The Fountainhead and Howard Roark, a book that means many things to many people. It’s probably most cited as a bible for capitalism and individualism, but as an architect in architecture school, I saw Roark as an archetype for creative integrity.

The term “creative destruction” often applies to economics, but I think it’s just as applicable to writing and art; removing the old makes room for the new.

These 8 roles fall into two spheres of work, prompt engineering and prompt architecture, and I think I’ve done enough of both to articulate the difference. I see engineering as the act of building interfaces, programs, and databases so that someone can write and test prompts at scale, where architecture covers (a) designing the overall input-output pipeline, (b) reading essays to make frameworks and gather data, and (c) using the tools of the engineer to actually refine the system. Currently I’m doing it all, but I know the feedback would get better faster if I could focus entirely on prompt engineering. If you believe in this project, have a technical background, and are interested in collaborating in some form, send me an email: michael@michaeldean.site.

Joke credit goes to Alex Dobrenko`

I have a draft for an essay called “is quantification evil?” I have some friends who think it is, and I sense that a lot of people think it is. I acknowledge the danger of focusing on the wrong metrics, but would also love to write about my childhood love of numbers. At 4 years old I was a recreational counter: I just counted upwards for fun, to see how high it went (I didn’t yet grasp infinite). After I stopped, I’d remember the number, and then continue the next session. I think I passed 10k. At 5 years old, I organized a Kindergarten baseball league and kept statistics. Etc.

Accuracy = how close does an AI score match my own scores?; Precision = over many iterations, how close are the scores together?; Reliability = over many iterations, how bad is the worst score? Now I need to develop a way to test the usefulness of the feedback generated, which is harder and less reducible to a clean metric. TBD.

This new approach is based on a counter-intuitive insight: more context = less determinism. As new models come out, the context window is rapidly increasing (it’s now between 10-100 million tokens). But the ContextRot paper shows that after 1,000 tokens, reliability radically diminishes. These model reports claim to pass the “needle in a haystack test” for up to 10 million tokens, but this only applies for exact syntax matching (if the prompt is “What if your favorite color?” it’s able to find “my favorite color is blue” in a massive haystack). But for most use cases, including essay feedback, it’s all about semantic matching.

The Internet made readers scared of paragraphs. Paragraphs are fine in a book or essay because they are arranged in a single linear track. By contrast, a website is non-linear, and so readers get analysis paralysis. Any time they read, they’re subconsciously thinking “will I gain more value by stopping and reading this or by navigating somewhere else in the site?” This constant questioning makes it hard to get into a flow. The choose-your-own-adventure UX has consequences. It’s responsible for the single-sentence paragraphs that have dominated copywriting, and it’s infected the online essay format.

I promised a friend I’d publish this two weeks ago, but I missed it. He got seriously disappointed, which I appreciated. I asked him to promise that, if I don’t publish by the 15th, he would never speak to me again. That’s a real punishment, and perhaps the reason why I sent this today. Figure out what it takes to make your arbitrary deadlines real.

Having read a few drafts of this essay, version 7.2 is proof of the thesis. Lots of darlings killed, but this is far and away the best version of the essay.

This insight will stick with me: "Once you grasp the nature and magnitude of an original sin, the only way forward is destruction. There is no degree of polish or patchwork that can fix a flawed foundation."

I love this—it’s worthy of the Delphic Oracle: “If you believe in the spirit of iteration, then design is 50% destruction.”

Hemingway’s first wife accidentally left a satchel with the manuscripts of all his as-yet unpublished short stories on a train in France. They were never recovered.

So Hemingway had to re-write them all from scratch, putting the material through the imaginative crucible you describe and initiating the alchemical dance of thesis and form, essence and appearance, substance and accident.

That’s how Hemingway’s art reached greatness.

The prospects for Essay Architecture are just as dazzling!