$9 essay coach

The feedback you won't get from your friends, family, and chatbots

The submission portal for the $10,000 Essay Architecture Prize is open! In case you missed it, here is the announcement, the prompt, and now the competition website. After you upload your essay to get scores and feedback, you’ll see a “Submit” tab where you can enter your essay. Also, the deadline is extended to Sunday, November 23rd.

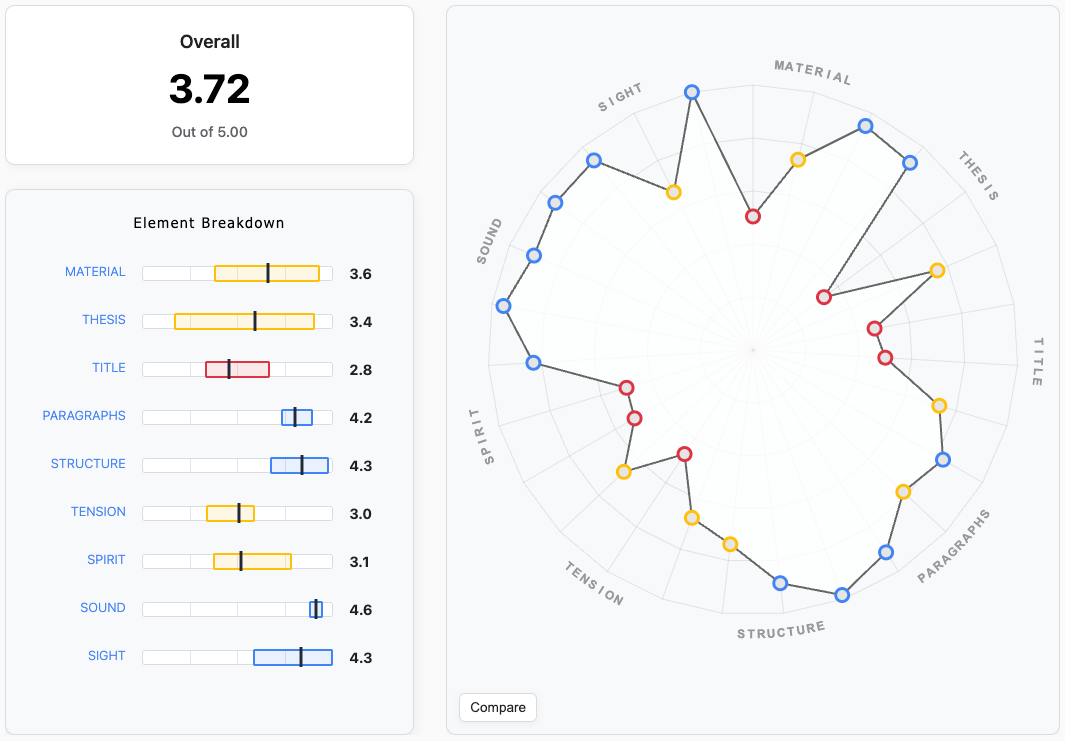

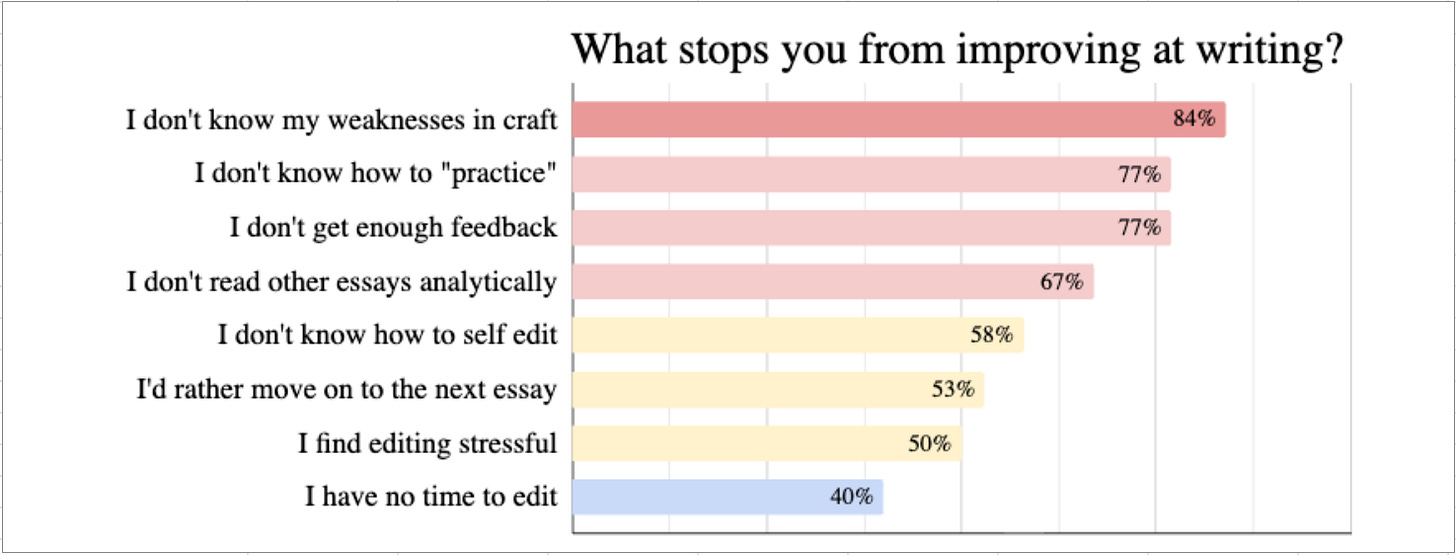

I’ve been building an app for writers all year, and a few months ago I sent out a survey1: 95% of you said ‘essays as creative practice’ was the main reason you write, 80% said ‘improving the quality of your writing is 5/5 important,’ and the #1 thing stopping you is that ‘you don’t know the weaknesses in your craft.’

How are you supposed to find your blindspots? A writer is too close to the work—too enmeshed in every idea, too enamored by every turn of phrase, too entangled in their own context—to see it the way a stranger does. This is what feedback is for. The problem is that friends, family, and chatbots veer towards sycophancy; they flatter more than they challenge. To get critical insights into your writing, you could find a coach or developmental editor, but they’re often expensive or unavailable. My own go-to editor, the one willing to toss me feedback grenades, has disappeared into the Rocky Mountains. And as a developmental editor myself, I know the problem: a deep diagnosis can take days, and I charge upwards of $150/hour. Some college essay coaches charge $1,000/hour.

The main goal of Essay Architecture is to help you see the invisible patterns in your writing. Since it’s effectively an always-available $9 essay coach, I find myself reflecting on what exactly coaches do. How do they unlock mastery? (Is it really just motivation and accountability, or is it about technique?) What are the differences and challenges when trying to recreate a coach with AI? And what happens when society cracks Benjamin Bloom’s Two Sigma Problem and everyone suddenly gets access to infinite coaching? Naturally, I thought back to my own coaches, and there’s one that stands out: my private batting coach from high school, Fat Joe. In 9th grade I didn’t make the JV team but was offered a spot as waterboy, and so I sought professional intervention. Not only did Joe teach me how to really swing a bat, I learned the fundamentals of how to practice, and how to master technique; this applies to anything, especially writing.

Perfect practice makes perfect:

Every week my dad would drop me off at Joe’s house, and I’d walk through the side gate, back into his backyard baseball dojo, filled with mesh structures, metal contraptions, and of course, hundreds of loose baseballs. He was loud and jolly, intimidating but patient, always ready to roast me and laugh it off. He called himself Fat Joe, possibly because of his size, or possibly because of his resemblance to the rapper, Fat Joe, also Puerto Rican.

Before we started our first session, he asked me, “So Michael, practice makes perfect, right?” Not expecting the trap, I answered, “definitely.” “WRONG!—” he yelled with a grin. “Practice doesn’t make perfect, PERFECT practice makes perfect.” I didn’t know what this meant, or that it was coined by Vince Lombardi.

He explained that if you practice every day with bad technique, you don’t just fail to improve, you internalize habits that are hard to notice and even harder to change. This might explain why, after obsessing over baseball for 10 years—watching it daily, playing in multiple leagues each season, and hanging out in batting cages at summer camp—I still sucked. I may have swung a bat over 25,000 times, but with each bad swing I locked myself into mediocrity.

Fat Joe was able to diagnose my problems immediately: bat slouched, elbow down, barely stepping, lunging forward, and (worst of all) not twisting my back leg. He knew all the mechanics of a perfect swing, but more importantly, he knew specific drills to isolate and fix each part. His exercises were eccentric, but who was I to question him? I didn’t make JV and his son was in the minor leagues of the New York Yankees.

“Squish the bug!” Joe was pitching fastballs, but I wasn’t allowed to hold the bat. My arms were behind my back, the bat between them like a skewer, and my task was to keep my eye on the ball as I twisted my back right ankle as hard as I could to squish an imaginary cockroach. “C’mon, SQUISH it!” He’d tell me to imagine how gross the bug was, to put all my weight into it, to make sure it was dead. The point was not to hit the ball; the point was to isolate the part of my swing that was the weakest.

Once my ankle rotation improved, we switched to the next technique, and then the next. He seemed to have drills for everything. Sometimes he’d put the ball on a tee and make me swing with one arm. Sometimes he’d pitch from the side. Sometimes from behind. I was frequently wrapped in tension bands. If I’d slip back into bad form, he’d nudge me, taunt me, push me, or surprise peg me with a tennis ball at 50 miles per hour.

At the end of every session, he’d recite his mantra, “practice doesn’t make perfect, perfect practice makes perfect.”

In 10th grade, everyone was surprised to see the waterboy turn into Aaron Judge. That’s a gross exaggeration, but really I made the starting lineup, batted 2nd, and had the highest average on the team. It came out of nowhere; no one saw the ~300 swings per week under Fat Joe’s supervision. I never played baseball again after that breakout season—thanks to a freak snowboarding accident that broke my arm completely in half—but I learned something more valuable than a swing: mastery doesn’t come from repetition; it comes from targeted, corrective repetition. If you want to get really good at something, you don’t just show up for a scrimmage every week, you find a coach to show you what and how to practice.

The idea that 1-on-1 instruction could turn the average kid into the leader of the pack isn’t a new idea, it’s the conclusion of Benjamin Bloom’s research. In 1984, he found that students with a tutor scored better than 98% of kids who learned in a conventional classroom model. Bloom titled his paper The Two Sigma Problem to emphasize the challenge in finding a scalable, cost-effective way to replicate the effects of coaching.

For almost five years now, I’ve been a developmental editor—I work 1-on-1 with writers to bring an idea to its peak form, and to help them see the patterns in their prose—but there’s a limit to the number of people I can help. The last year has been a blitz to code everything I know about writing into a single app. Today I’m excited to announce that the Essay Architecture app is live.

Find the invisible patterns in your craft:

Unlike most AI writing tools—which are inevitably slanted by markets to become autocomplete tools for businesses—the mission here is to make something that helps you improve. This is an educational tool, not a ghostwriter: you can’t talk to it, you can’t ask it questions,2 and it definitely won’t write your sentences. It does one thing: it evaluates your uploads and offers insights into your craft. This is built for a subset of writers who publish online, respect the process, and know the value in being able to compose a great essay.

Think of this like Fat-Joe-as-an-app but for essays: it gives you a holistic evaluation of your writing mechanics, it finds your weaknesses in technique, and then gives you specific guidance to improve.

This will not automate, accelerate, or simplify your process; it will guide you through the labyrinths of editing that you typically avoid. At a minimum, it gives you actionable feedback; and if you’re a paid subscriber, it gives you “editing lenses” that isolate one pattern at a time. Instead of reading from the top and hoping you’ll find ways to fix your draft, you could try squish-the-bug-style editing drills. What if you only workshop the opening sentence of each paragraph? What if you read it out loud and edit for sound? What if you put every sentence on its own line, read the right edge, and edit for rhythm? What if you scan for concreteness, making sure each paragraph has an image, a reference, or a personal experience?

For a computer to analyze your techniques and make recommendations, it requires quantification, and I imagine that could bring up trauma from your school days. Do essays really need to be scored through a shared standard? The critical nuance here is the Paradox of Standardization: the right kind of standards enable customized learning at scale. It’s possible we all hate standardization because we’ve been trapped in boneheaded systems. A bad standard prescribes a specific form (like the ‘Five Paragraph Essay’), while a good standard describes the nature of a solution, allowing for creativity and variety. Also, a standard is only useful to the degree that it shares granular sub-scores that enable specific learning paths. It should be less about ‘judge my skills’ and more about ‘show me where to focus.’

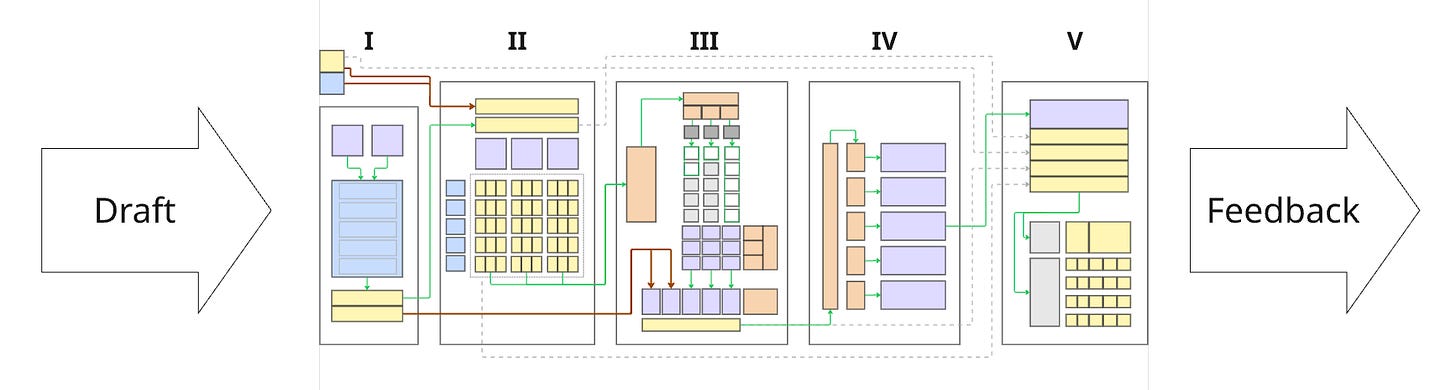

When you try the app, you’ll notice a pattern score comes in every 45 seconds, and you’ll naturally wonder, can I trust these scores? Large language models are dubious judges of quality. Even though training runs have exposed them to trillions of words, including all of the classics, it does not know what is “good,” only what is probable. Experiment with ChatGPT, and you’ll notice that it loves slop and it can’t reproduce its scores: if you feed it the same essay multiple times (in separate windows), and ask for a 1-5 score, you’ll get scattered results: 3.25, 2.75, 3.45. However, if you significantly narrow the scope, AI is powerful at analysis. For example, if you give o4 just one paragraph and a specific rhyme analysis algorithm, it’s precise and repeatable.

Why the discrepancy? It’s counterintuitive, but the more context you give, the less reliable its judgments. Since the latest models have million-token context windows, writers are quick to upload 10,000 word style guides and example libraries—but actually, this is bad practice. The Context Rot paper (July 2025) showed that the reliability of semantic analysis dramatically drops after 1,000 tokens! This means a single essay is usually too big to meaningfully process. To address this, I built Essay Architecture in a way that’s fundamentally different from ChatGPT, Claude, or Gemini: it breaks your essay down into smaller units—paragraphs—and runs 1k-10k atomic evaluations on each upload. Each of the 27 patterns has its own algorithm, and I rigorously test these to see if it matches my own scores and intuition.

Sounds neat, but does it actually work? My goal by EOY is to have public metrics so you know exactly how much you can trust the system. For now, I have rough estimates. The Precision Score is ~96-99%, meaning you get results within +/- 0.1 if you upload the same essay twice (Claude scores ~83%). The Accuracy Score is ~73-91% (compared to Claude and ChatGPT which scores in the 60s). What this tells me is that Essay Architecture thinks in a semi-deterministic way, but there’s still a lot of tedious testing I need to do for it to match my control set more closely. I still need to establish a Feedback Score to measure the usefulness of the suggestions, along with a Slop Index for each pattern. The goal is to keep improving this until it can reliably guide anyone from a first draft to the best thing they’ve ever written, repeatedly.

What are the implications of solving Bloom’s Two Sigma Problem for writers? It could mean that someone’s slope of progress could radically increase. Less writers would give up. It would take a skill that seems impossibly difficult and make it manageably difficult; always challenged, but never confused, never hopeless. Regardless of our escalating slopfest, it is a good thing to bring more people onto a quest to master something. By approaching mastery, you cultivate a transferable skillset—including discipline, focus, presence, patience, resilience, and determination—that touches areas of life well beyond your domain. We should shift our question from ‘what happens if AI makes masterpieces?’ to ‘how can we build AI to train a new generation of masters?’

This is the mission of Essay Architecture. I’m two years into this, and there’s still so much to do, fix, and build, but it’s great to see it helping writers already. Here’s my first (unsolicited) testimonial:

“I uploaded my first essay to your software yesterday. I used a Substack post I wrote a few months ago that I was quite proud of and others enjoyed. And...your software tore it to shreds! For 2 minutes I sulked defensively...then I went into learning mode. It’s truly a great tool and you should be proud. I woke up this morning with a flood of ideas on how to improve it, which on a higher level is giving me more insights about myself. Thank you for the invitation/challenge to try it!” – Bob Gilbreath

And here’s another:

“Mind blown. I just got the best essay feedback I’ve ever received and it didn’t come from a person. It came from @MichaelDean_0’s Essay Architecture.” – James Vermillion III

If you’re curious to see the invisible architecture behind your essay, you should give Essay Architecture a try. It’s only $9. And if you like it, you can get it for as low as $2/draft when you buy upload credits in bulk.

Thanks again for being a reader of Essay Architecture! This post marks the beginning of a platform, and so here’s the range of things you can consider doing:

First, check out the new website.

Buy some upload credits ($2-9) and use the app as your essay coach. If you want to share feedback (bugs, feature ideas, testimonials), you’ll find a “Contribute” icon on the right of the website’s navigation bar.

Write the best essay you can and submit it to the Essay Architecture Prize to win $10,000. The deadline is November 23rd, 2025.

Become a paid subscriber and unlock the textbook, which includes 24,000 words on a pattern language for essays, and will soon begin updating with examples ($10/month)

Join Essay Club to start a long-term writing habit ($300/year)

Read the mission statement and share feedback here to help shape it.

Footnotes:

If you filled out the survey from earlier this year, thank you! I didn’t have enough bandwidth to organize a full-scale beta before this launch, but hold tight, and I will be sending you an email with a free upload credit.

Eventually, there might be a chat feature where you can ask questions about whatever you upload (because conversation is a big part of coaching too!), but I want to be careful and intentional about building this. Once you create a chat interface, the UX possibilities are boundless, and it becomes so much harder to test and make useful.

Michael, I'm in awe of your well-organised, clear thinking, and I'm rushing to meet the deadline for the essay competition, since I saw it late. I hope to upload my essay to your architecture grading machine later today and am very excited to see what it responds. Meanwhile, some questions are running through my mind.

I'm assuming that all the essays that we, enthusiasts, upload will further train your machine. But I wonder what you trained it on initially. I seem to remember reading in one of your pieces that you used 1000s of essays. You seem to be a generous person, but if you trained your machine on other people's essays, how do you go about compensating them? How does it work with copyright? And what is the underlying AI? Is the analysis done purely by algoritm, if so, what is the AI part of it?

These questions are not covert judgement. I'm just curous and trying to form an opinion, given all the controversy around LLMs and other AI. Anyway. Time to get back to my essay!

Excited to use this! I joined your session for Act Two and am just getting started with Substack as a side project, so this sounds perfect.

As for the day job… I work with a team of AI engineers who built an essay marking assistant for teachers using a very similar methodology! One potential difference in approach was we had a strong feedback loop between labelling and iterating on the prompt. Happy to share more info on what they did if helpful